Gayadas de Caliman13

caught my eye surfing.....

Friday, August 17, 2007

Cuando el precio alto es la "carnada".

FASHION & STYLE |

| When High Price Is the Allure By RUTH LA FERLA Published: August 9, 2007 |

|

|

| WHEN readers leaf through the September issue of Vogue, which arrives on newsstands next week, they will encounter a Prada mohair twin set tagged at $2,925; a chunky Giles sweater, at $3,675; and a supersize Marc Jacobs bracelet, at $2,180. And as fall looks begin trickling into stores this month, shoppers will find basic designer sheath dresses selling for $1,200, coats for just under $4,000 and designer sunglasses for $500 or more. This is the fourth consecutive autumn season in which a weak dollar has meant higher prices for designer clothing, much of which is made in Europe or stitched from fabrics imported from European mills. As the value of the dollar shrinks against the euro, prices continue to climb, with retailers citing hikes of as much as 15 percent for shoes and bags this year compared with last. Yet, merchants and manufacturers have seen surprisingly little resistance in recent seasons to the cost of luxury goods. So strong is the demand for cashmere car coats and crinkled patent leather bags at Barneys New York that that two firms — one from Dubai, the other from Japan — are in a bidding war this month to acquire the store for close to $1 billion. The luxury conglomerate LVMH, the owner of Louis Vuitton, had net profits for the first half of 2007 of $1.11 billion, up 2 percent from a year ago. Profits at the parent of Gucci and at Prada are also up. Those brands owe part of their success to shoppers with caviar taste who have come to view extravagant prices as an enduring, if unwelcome, fact of life. At the same time, another consumer cohort is driving the trend, shoppers for whom a high ticket can in itself be an inducement to buy. Just as makers of premium ice cream have persuaded consumers to pay $4 for a cone instead of 90 cents, and California vintners convince them that a $100 cabernet is better than a $50 bottle, the makers of designer clothing know that high prices can cast a spell. "Price certainly plays into a product's allure," said Robert Burke, a retail consultant in New York. "For certain people, the higher the price, the more attractive the item becomes." |

|

|

| An exorbitant price can confer exclusivity. "People are willing to pay a significant amount of money to make sure they don't see their purchase on other people," Mr. Burke said. Or to ensure that their friends will recognize its provenance. "Price is part of the status of certain luxury items," said Marvin Traub, a retail consultant in New York. Mr. Traub, who visited Moscow in March, noticed that people there were fascinated not by how little but how much was paid. To some extent, Mr. Traub noted, "that sort of thinking translates here, too." Among merchants and manufacturers, consumer psychology can be as significant as economics in setting prices. "Luxury makers are not necessarily forced to raise prices above the exchange-rate factor, but sometimes they do," said Milton Pedraza of the Luxury Institute, a research group in New York. "Why? They know that consumers are resilient. For manufacturers, it's really about asking for a price increase because you can." Those remarks resonate with Jeffrey Kalinsky, a specialty retailer who owns fashion emporiums in New York and Atlanta. Mr. Kalinsky, who is also the director for designer merchandizing of Nordstrom, does not pretend to speak for his customers. But he shares their sometimes-irrational passions. He recalled that as long as 20 years ago, when he was in his mid-20s, he would "just walk into a store and see a sweater, and something inside of me would say, 'Oh, I hope I can afford it. I bet it's at least $800.' "That sweater would be $1,100," Mr. Kalinsky confided, "but, miraculously, then I would want it more." In some cases, manufacturers adjust prices upward to make sure that their goods hang in good company, displayed alongside prestigious luxury brands. "They tack on a healthy premium, because they want to maintain the exclusivity of the brand," Mr. Pedraza said. "The customer pays for that cachet." Susan Sokol, the president of Vera Wang, acknowledged that while it is important to maintain a range of prices within a collection, "it is extremely critical to understand price positioning and to be very strategic about it. "If I know our customer is buying Miu Miu or Dries van Noten," she said, "we have to price accordingly." The appetite for high-end wares has been a boon to retailers, who need to sell fewer of a given item to turn a handsome profit. The higher the price, the higher the margin, Mr. Burke pointed out: "It's much easier to sell five of something really expensive than 20 of something less expensive." Markups, he said, have remained much the same since last year. |

|

|

| A stroll through several high-end stores in Manhattan this week turned up prices that might be the equivalent of a down payment on a minivan. At Jeffrey, in the meatpacking district, a raglan-sleeve black jersey Lanvin dress was $2,455, a Shawn Collins thermal knit sweater $995. Barneys offerings included a Balenciaga leather bag with fancy grommets, $1,725; Lanvin leather ballet flats, $530; and Marc Jacobs cuffed leather ankle boots, $995. At Bergdorf Goodman, a Stella McCartney turtleneck devoid of trim sells for $995, and her cable-stitched sweater for $1,495. A pair of Kieselstein-Cord sunglasses is tagged at $595. Far from daunting, such a ticket might be downright seductive to customers, Ms. Sokol said. "When you are looking at a handbag or even a pair of sunglasses, a high price can have inherent snob appeal." Consumers tell themselves, Ms. Sokol went on, " 'If those glasses are $150, I'm not going to be as interested as if they are $350.' " That is not to say that consumers are indifferent to price. Many are making emotional adjustments, finding ways to balance a love of fashion with the reality of its increasingly exorbitant cost. Eunice Ward, a lawyer in Chicago with a taste for quirky labels like Dolce & Gabbana and Stella McCartney, pays full price only for items that resonate with her sense of style. During a recent shopping trip, she spied a Yohji Yamomoto sweater. "I knew it would fit with my wardrobe and update everything," she said, "that it was going to be my workhorse for fall. "I didn't even check the price at first. I knew I would love it, and I didn't care." At Saks Fifth Avenue in Manhattan last week, Jessica Lee darted among the racks, gazing avidly at a champagne-colored Miu Miu cocktail dress, scarcely bothering to look at its $1,250 tag. "Fashion's gotten more expensive," Ms. Lee said, a fact as inevitable, and untroubling, to her as the tide. "The economy is good," said Ms. Lee, who works for a private equity firm in Manhattan. "I've made a lot more over the past year than before, and so I have more purchasing power." Kate Strachan appeared to be more circumspect. As a technical designer for a fashion house, she is well acquainted with the price of style. "I know a lot of quality, craftsmanship and time goes into some of these pieces," Ms. Strachan said. Regardless, she is determined to put a cap on her spending. Combing the racks at Saks, she sighed wistfully: "I can't afford these kinds of things, so usually I buy what I need most. This year that would be a winter coat." Then with a self-mocking smile she added, "Of course there are times when I'll splurge." |

El Renacimiento de Medellín. NYT.

TRAVEL Next Stop - Medellín, Colombia |

| A Drug-Runners' Stronghold Finds a New Life By GRACE BASTIDAS Published: August 12, 2007 |

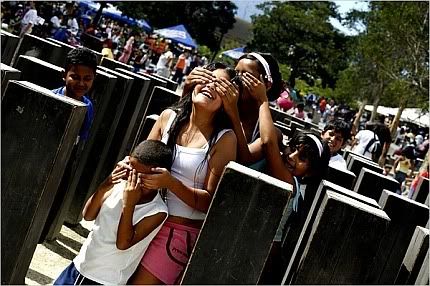

Buskers play carrilera music downtown. Not long ago, this scene would have been unthinkable in Medellín. Photo: Paul Smith for The New York Times |

| IT was Thursday evening in Medellín and the open-air bars and cafes along fashionable Lleras Park were overflowing with after-work singles. At Triada, a stylish lounge with an orange neon bar and low-slung couches, laughter filled the subtropical air along with the deep-toned drumming of cumbia music. From around the corner, a small group of motorcyclists screeched by, their shiny engines puttering like machine guns. No one flinched, and the party kept rolling. |

Wishes Park is an oasis of concrete floors and polished cherry-wood tables, with a planetarium and a music hall where the Medellín Philharmonic rehearses. Photo: Paul Smith for The New York Times |

Not long ago, this scene would have been unthinkable in Medellín, once considered the most dangerous place on earth. During the 1980s, Medellín, Colombia's second largest city, was home to the drug lord Pablo Escobar, whose infamous cartel turned the city into a bloody battleground and the world's cocaine capital. Gangs roamed the narrow streets, extortionists preyed on the city's residents and narcotics traffickers staged attacks against police. "You couldn't step outside," said Bibian Gomez, 28, a commercial real estate broker who sought refuge in the resort town of Cartagena at the height of the violence. "Whenever you saw a young guy on a motorcycle you thought that he was an assassin." |

Tourists ride a gondola up to Santo Domingo Savio, a once impenetrable slum of tin-roofed shanties on a hillside in northern Medellín. Photo: Paul Smith for The New York Times |

| But in the last decade, this city of two million, with its beautiful colonial architecture and year-round spring-like weather, has awakened from its drug nightmare. Mr. Escobar and his minions are gone and the cocaine trade has been largely dispersed. Bullet-riddled neighborhoods are coming to life with art museums and well-designed parks. And the constant rumble of construction — new shopping malls, flashy casinos and luxury hotels — can be heard throughout the city. |

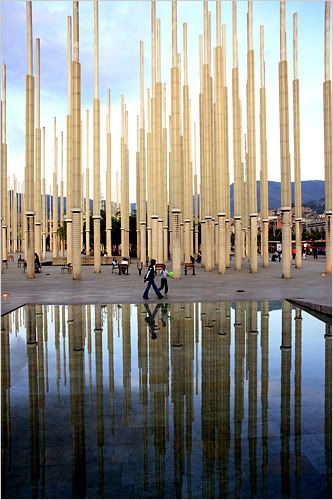

The Park of Lights, which resembles a giant birthday cake when all 300 of its 72-foot-tall columns are illuminated at night. Photo: Paul Smith for The New York Times |

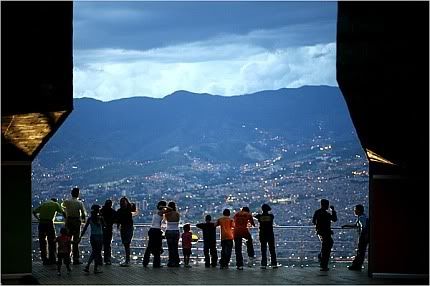

| The renaissance is most noticeable in Santo Domingo Savio, a once impenetrable slum of tin-roofed shanties on a hillside in northern Medellín. Though pockets are still marred by a dilapidated jumble of crumbling cinderblocks and concrete stairs, it is now home to paved roads, colorful murals and the gleaming new Parque Biblioteca España. The hulking opal structure has a library, an auditorium, computer rooms, a day care center and an art gallery. Getting there has gotten much easier, too. What once took an hour on a rickety bus, now takes 10 minutes, thanks to a shiny gondola that opened in 2004, part of a growing public transportation network that is uniting the city and making it more accessible, especially for the poor. |

Children play in the Zen-themed Barefoot Park. Photo: Paul Smith for The New York Times related |

| On a recent afternoon, Santo Domingo Savio exuded the easygoing revelry of a small state fair. There were uniformed school children jumping rope, elderly men selling fresh slices of mango, and young couples strolling hand in hand admiring the views of the city below — a landscape of verdant pastures crowned by scattered high-rises and restored 19th-century buildings. These days, the view also includes construction cranes, largely because of Medellín's iconoclast mayor, Sergio Fajardo, who has commissioned renowned Colombian architects like Giancarlo Mazzanti and Felipe Uribe to construct libraries and innovative parks in neglected neighborhoods. |

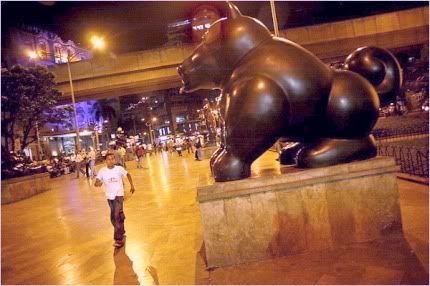

The busy Plaza Botero is home to 23 bronze sculptures by the Colombian artist Fernando Botero, frequently referred to as Latin America's most important living artist. Photo: Paul Smith for The New York Times |

| The centerpiece is Explora Park, a 398,000-square-foot science and technology park in the northeastern end of town that will be home to one of South America's largest aquariums when it opens partially in late October. A block south is the sleek Wishes Park, an oasis of concrete floors and polished cherry-wood tables, with a planetarium and a music hall where the Medellín Philharmonic rehearses. Movies are shown outdoors there. Other education-minded parks, all situated along the improved Metro system, include the Zen-themed Barefoot Park, which invites visitors to walk through a bamboo forest and then dip their feet in cascading water fountains; and the Park of Lights, which resembles a giant birthday cake when all 300 of its 72-foot-tall columns are illuminated at night. |

Tourists view the lights of Medillín from the Parque Biblioteca España. Photo: Paul Smith for The New York Times |

| Art has also flourished, led by a native-son, Fernando Botero, frequently referred to as Latin America's most important living artist. In 2000, he donated 137 of his works to the Museum of Antioquia (Carrera 52 No. 52-43, +57(4)251-3636; www.museodeantioquia.org), including a painting that depicts a pudgy Pablo Escobar toppled by bullets. But Medellín's transformation may be most apparent at night. During the cocaine days, those who ventured onto the city's lifeless, grid-like streets after hours encountered a Wild West showdown of trigger-happy capos. Now, cafes and bars spill onto the sidewalks, lending a festive and carefree vibe to the balmy evenings. Sprawling nightclubs draw thousands with thumping Latin music that keeps the young crowd dancing until dawn |

| On a recent Thursday night at the popular Mango's (Carrera 42 No. 67A-151; 57-4-277-6123), a ranch-style disco with cowboy memorabilia and waiters dressed to match, an eagerly anticipated three-day weekend was about to turn into a four-day party. A cluster of young clubgoers ordered rum-and-coke cocktails as the rhythms of reggaetón and vallenato shook the foggy dance floor. It was 3 a.m. but you couldn't tell by the crowd's infectious energy. They were clearly in it for the long haul, as if making up for lost time. |

Thursday, August 16, 2007

Rompiendo el paradigma de Malthus.

SCIENCE |

| In Dusty Archives, a Theory of Affluence By NICHOLAS WADE Published: August 7, 2007 |

|

|

| For thousands of years, most people on earth lived in abject poverty, first as hunters and gatherers, then as peasants or laborers. But with the Industrial Revolution, some societies traded this ancient poverty for amazing affluence. Breaking Out of a Malthusian Trap Historians and economists have long struggled to understand how this transition occurred and why it took place only in some countries. A scholar who has spent the last 20 years scanning medieval English archives has now emerged with startling answers for both questions. Gregory Clark, an economic historian at the University of California, Davis, believes that the Industrial Revolution — the surge in economic growth that occurred first in England around 1800 — occurred because of a change in the nature of the human population. The change was one in which people gradually developed the strange new behaviors required to make a modern economy work. The middle-class values of nonviolence, literacy, long working hours and a willingness to save emerged only recently in human history, Dr. Clark argues. Because they grew more common in the centuries before 1800, whether by cultural transmission or evolutionary adaptation, the English population at last became productive enough to escape from poverty, followed quickly by other countries with the same long agrarian past. Dr. Clark's ideas have been circulating in articles and manuscripts for several years and are to be published as a book next month, "A Farewell to Alms" (Princeton University Press). Economic historians have high praise for his thesis, though many disagree with parts of it. "This is a great book and deserves attention," said Philip Hoffman, a historian at the California Institute of Technology. He described it as "delightfully provocative" and a "real challenge" to the prevailing school of thought that it is institutions that shape economic history. Samuel Bowles, an economist who studies cultural evolution at the Santa Fe Institute, said Dr. Clark's work was "great historical sociology and, unlike the sociology of the past, is informed by modern economic theory." The basis of Dr. Clark's work is his recovery of data from which he can reconstruct many features of the English economy from 1200 to 1800. From this data, he shows, far more clearly than has been possible before, that the economy was locked in a Malthusian trap _ — each time new technology increased the efficiency of production a little, the population grew, the extra mouths ate up the surplus, and average income fell back to its former level. This income was pitifully low in terms of the amount of wheat it could buy. By 1790, the average person's consumption in England was still just 2,322 calories a day, with the poor eating a mere 1,508. Living hunter-gatherer societies enjoy diets of 2,300 calories or more. "Primitive man ate well compared with one of the richest societies in the world in 1800," Dr. Clark observes. The tendency of population to grow faster than the food supply, keeping most people at the edge of starvation, was described by Thomas Malthus in a 1798 book, "An Essay on the Principle of Population." This Malthusian trap, Dr. Clark's data show, governed the English economy from 1200 until the Industrial Revolution and has in his view probably constrained humankind throughout its existence. The only respite was during disasters like the Black Death, when population plummeted, and for several generations the survivors had more to eat. Malthus's book is well known because it gave Darwin the idea of natural selection. Reading of the struggle for existence that Malthus predicted, Darwin wrote in his autobiography, "It at once struck me that under these circumstances favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. ... Here then I had at last got a theory by which to work." Given that the English economy operated under Malthusian constraints, might it not have responded in some way to the forces of natural selection that Darwin had divined would flourish in such conditions? Dr. Clark started to wonder whether natural selection had indeed changed the nature of the population in some way and, if so, whether this might be the missing explanation for the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution, the first escape from the Malthusian trap, occurred when the efficiency of production at last accelerated, growing fast enough to outpace population growth and allow average incomes to rise. Many explanations have been offered for this spurt in efficiency, some economic and some political, but none is fully satisfactory, historians say. Dr. Clark's first thought was that the population might have evolved greater resistance to disease. The idea came from Jared Diamond's book "Guns, Germs and Steel," which argues that Europeans were able to conquer other nations in part because of their greater immunity to disease. In support of the disease-resistance idea, cities like London were so filthy and disease ridden that a third of their populations died off every generation, and the losses were restored by immigrants from the countryside. That suggested to Dr. Clark that the surviving population of England might be the descendants of peasants. A way to test the idea, he realized, was through analysis of ancient wills, which might reveal a connection between wealth and the number of progeny. The wills did that, , but in quite the opposite direction to what he had expected. Generation after generation, the rich had more surviving children than the poor, his research showed. That meant there must have been constant downward social mobility as the poor failed to reproduce themselves and the progeny of the rich took over their occupations. "The modern population of the English is largely descended from the economic upper classes of the Middle Ages," he concluded. As the progeny of the rich pervaded all levels of society, Dr. Clark considered, the behaviors that made for wealth could have spread with them. He has documented that several aspects of what might now be called middle-class values changed significantly from the days of hunter gatherer societies to 1800. Work hours increased, literacy and numeracy rose, and the level of interpersonal violence dropped. Another significant change in behavior, Dr. Clark argues, was an increase in people's preference for saving over instant consumption, which he sees reflected in the steady decline in interest rates from 1200 to 1800. "Thrift, prudence, negotiation and hard work were becoming values for communities that previously had been spendthrift, impulsive, violent and leisure loving," Dr. Clark writes. Around 1790, a steady upward trend in production efficiency first emerges in the English economy. It was this significant acceleration in the rate of productivity growth that at last made possible England's escape from the Malthusian trap and the emergence of the Industrial Revolution. In the rest of Europe and East Asia, populations had also long been shaped by the Malthusian trap of their stable agrarian economies. Their workforces easily absorbed the new production technologies that appeared first in England. It is puzzling that the Industrial Revolution did not occur first in the much larger populations of China or Japan. Dr. Clark has found data showing that their richer classes, the Samurai in Japan and the Qing dynasty in China, were surprisingly unfertile and so would have failed to generate the downward social mobility that spread production-oriented values in England. After the Industrial Revolution, the gap in living standards between the richest and the poorest countries started to accelerate, from a wealth disparity of about 4 to 1 in 1800 to more than 50 to 1 today. Just as there is no agreed explanation for the Industrial Revolution, economists cannot account well for the divergence between rich and poor nations or they would have better remedies to offer. Many commentators point to a failure of political and social institutions as the reason that poor countries remain poor. But the proposed medicine of institutional reform "has failed repeatedly to cure the patient," Dr. Clark writes. He likens the "cult centers" of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to prescientific physicians who prescribed bloodletting for ailments they did not understand. |

|

|

| If the Industrial Revolution was caused by changes in people's behavior, then populations that have not had time to adapt to the Malthusian constraints of agrarian economies will not be able to achieve the same production efficiencies, his thesis implies. Dr. Clark says the middle-class values needed for productivity could have been transmitted either culturally or genetically. But in some passages, he seems to lean toward evolution as the explanation. "Through the long agrarian passage leading up to the Industrial Revolution, man was becoming biologically more adapted to the modern economic world," he writes. And, "The triumph of capitalism in the modern world thus may lie as much in our genes as in ideology or rationality." What was being inherited, in his view, was not greater intelligence — being a hunter in a foraging society requires considerably greater skill than the repetitive actions of an agricultural laborer. Rather, it was "a repertoire of skills and dispositions that were very different from those of the pre-agrarian world." Reaction to Dr. Clark's thesis from other economic historians seems largely favorable, although few agree with all of it, and many are skeptical of the most novel part, his suggestion that evolutionary change is a factor to be considered in history. Historians used to accept changes in people's behavior as an explanation for economic events, like Max Weber's thesis linking the rise of capitalism with Protestantism. But most have now swung to the economists' view that all people are alike and will respond in the same way to the same incentives. Hence they seek to explain events like the Industrial Revolution in terms of changes in institutions, not people. Dr. Clark's view is that institutions and incentives have been much the same all along and explain very little, which is why there is so little agreement on the causes of the Industrial Revolution. In saying the answer lies in people's behavior, he is asking his fellow economic historians to revert to a type of explanation they had mostly abandoned and in addition is evoking an idea that historians seldom consider as an explanatory variable, that of evolution. Most historians have assumed that evolutionary change is too gradual to have affected human populations in the historical period. But geneticists, with information from the human genome now at their disposal, have begun to detect ever more recent instances of human evolutionary change like the spread of lactose tolerance in cattle-raising people of northern Europe just 5,000 years ago. A study in the current American Journal of Human Genetics finds evidence of natural selection at work in the population of Puerto Rico since 1513. So historians are likely to be more enthusiastic about the medieval economic data and elaborate time series that Dr. Clark has reconstructed than about his suggestion that people adapted to the Malthusian constraints of an agrarian society. "He deserves kudos for assembling all this data," said Dr. Hoffman, the Caltech historian, "but I don't agree with his underlying argument." The decline in English interest rates, for example, could have been caused by the state's providing better domestic security and enforcing property rights, Dr. Hoffman said, not by a change in people's willingness to save, as Dr. Clark asserts. The natural-selection part of Dr. Clark's argument "is significantly weaker, and maybe just not necessary, if you can trace the changes in the institutions," said Kenneth L. Pomeranz, a historian at the University of California, Irvine. In a recent book, "The Great Divergence," Dr. Pomeranz argues that tapping new sources of energy like coal and bringing new land into cultivation, as in the North American colonies, were the productivity advances that pushed the old agrarian economies out of their Malthusian constraints. Robert P. Brenner, a historian at the University of California, Los Angeles, said although there was no satisfactory explanation at present for why economic growth took off in Europe around 1800, he believed that institutional explanations would provide the answer and that Dr. Clark's idea of genes for capitalist behavior was "quite a speculative leap." Dr. Bowles, the Santa Fe economist, said he was "not averse to the idea" that genetic transmission of capitalist values is important, but that the evidence for it was not yet there. "It's just that we don't have any idea what it is, and everything we look at ends up being awfully small," he said. Tests of most social behaviors show they are very weakly heritable. He also took issue with Dr. Clark's suggestion that the unwillingness to postpone consumption, called time preference by economists, had changed in people over the centuries. "If I were as poor as the people who take out payday loans, I might also have a high time preference," he said. Dr. Clark said he set out to write his book 12 years ago on discovering that his undergraduates knew nothing about the history of Europe. His colleagues have been surprised by its conclusions but also interested in them, he said. "The actual data underlying this stuff is hard to dispute," Dr. Clark said. "When people see the logic, they say 'I don't necessarily believe it, but it's hard to dismiss.' " |

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

Pasta con Ragú de Langostinos. NYT.

DINING & WINE |

| To Toss the Shells Is to Discard Flavor By Mark Bittman (The Minimalist) Published: August 15, 2007 |

| |

| SHRIMP shells pose a problem for good cooks. Leaving them on unquestionably enhances any shrimp dish, because their flavor is about as strong as that of the meat. Peeling shrimp at the table, however delicious, is a messy and sometimes finger-burning job. Removing the shells beforehand is easy enough, but for someone who cares about taste, discarding them seems akin to a sin. In some cases, you can eat the shells, which resolves this problem, but the shells must be thin and you and your guests adventuresome. Enter shrimp-shell stock, the most easily and quickly made stock there is, the one that provides the most punch for the least hassle. To make it, take the shrimp shells, cover them in water — you can add aromatics like carrots and onions, but it's hardly necessary — bring to a boil, simmer for a few minutes, and drain. When you are done you have essence of shrimp, a broth of a very high order, the perfect liquid for seafood risottos, stews and soups. It's perfect, too, for a shrimp-based pasta sauce. I first tried this little ragù — it has some of the same seasoning as the classic meat sauce of central Italy — in Venice, where it was made with the soft, small local shrimp and fresh pasta. At home, duplicating it was difficult for me: I make fresh pasta only for visiting dignitaries and they don't come over often. Fresh shrimp aren't easy to come by either: about 95 percent of the shrimp sold in the United States is frozen before sale. If you do luck into them, though, they will contribute mightily to the overall quality of the dish. Even with more conventional shrimp, the sauce is unusual and appealing. Fresh marjoram is definitely the herb of choice, though fresh oregano is an adequate substitute, and a handful of basil, which changes things a bit, is also good. In any case, do not use dried herbs here. The key, though, is the shrimp-shell stock, which reduces in the sauce and lends a kind of potency that's doubly enjoyable when you consider how economical it is. |

|

|

| Recipe: Pasta With Shrimp Ragù |

|

|

| Time: 40 minutes

Yield: 4 to 6 servings. |

El "Bolshoi" en Londres. "La Bayadera".

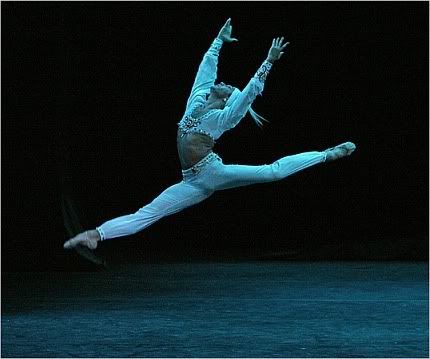

Dance Review 'La Bayadère' |

| The Bolshoi's Whiz Kids on Display in London By ALASTAIR MACAULAY Published: August 6, 2007 |

|

|

| LONDON, Aug. 4 — The Bolshoi Ballet's latest whiz kid, Ivan Vasiliev, is a colorful, engaging, 18-year-old firecracker who looks good as a smiling, fully clad and mustachioed slave in a virtuoso divertissement pas de deux in Act 1 of "Le Corsaire" or as a stone-faced, near-naked, painted-gold-all-over dancing statue in Act 2 of "La Bayadère." Hype before the Bolshoi's three-week season at the Coliseum here was wrong to exaggerate his potential by portraying him as another Baryshnikov. His jumps aren't actually of superhuman height, his landings are sometimes audible and (like other Bolshoi men during the company's first London week) his enthusiasm for ending solos with a particularly flamboyant effect sometimes leads him to fall over. But it is evident that he's a star, and it is likely that he has not yet shown London all he can do. (He is said to be a particularly dazzling turner.) My abiding memory of him is from his "Corsaire" solo, when he performed a zigzag with the same short but thrilling phrase on each diagonal — claiming the air in a hungry assemblé jump, landing with a pounce into a deep grand plié (knees fully bent apart), and at once exploding into a forward sissonne jump, legs split as he hung in the air, and all with an eager naughtiness in his eye. The contrasts — up-down-up, out-in-out — are maximized, and he relishes them. It's easy to imagine that he is an actor, an artist. One wants him, first, to inherit the great 20th-century roles that were made in the West on Nijinsky, Edward Villella, Helgi Tomasson, Mikhail Baryshnikov, and then to inspire new roles. Both of which might happen. In Moscow, the Bolshoi now dances a fast-expanding collection of 20th-century Western ballets, from choreographers ranging from Massine and Balanchine to Twyla Tharp. And the company is run by Alexei Ratmansky, who is as bright a hope as any today to bring new choreographic life to ballet. But how much of these new developments will the West get to see? When the Bolshoi visited during the Soviet era, Western critics could condescend charmingly to the terrible limitations of its repertory, mainly a mix of standard 19th-century works and homemade but dance-thin 20th-century story ballets. Today, however, you'd have to go to Moscow to see the real range of the company's repertory. In its Western appearances, the need for box-office income means that it mainly relies on the same kind of story ballets as before. Mr. Ratmansky is varying the selection of 19th-century ballets, and has made a hit with his staging of Shostakovich's full-length "Bright Stream" (seen in New York in 2005, in London in 2006 and again scheduled at the end of this London season). It is already possible to feel that a new kind of Bolshoi is emerging under his aegis, a Bolshoi less colossal in scale but with a much greater appetite for detail in both acting and dancing. |

|

|

| But it's also possible, amid these good signs, to overlook the bad ones. Nobody is likely to recall this season's second offering as its highlight. This was the classic "La Bayadère," as staged in 1991 by Yuri Grigorovich (Mr. Ratmansky's long-term predecessor). Until 1978, when the Kirov's full-length production of "La Bayadère" was first shown on Western television, few people had much clue what this 1877 story ballet, set in India, was like. For the last several years, as full-length "Bayadères" have become staples of international repertory, I've begun to feel that ignorance was bliss. The Bolshoi's version features, among other horrors, white children dressed as blacks (black-wrinkled tights, black-gloved sleeves and black curly wigs, but with faces lightly daubed in various pale coffee hues). I'd like to think that the old tradition of whites in blackface might work again if it was well done (e.g. white actors as Othello, now exceptionally rare in theater), but this looked too ludicrous to be even grotesque. Almost as irksome was the costume for the second-cast hero, Denis Matvienko. Since he is pale and blond, the company's idea of presenting him as an Indian warrior is to put him in lilac-colored pajamas with a plunging neckline on top of a tan-flesh-colored undervest. By contrast, the first-cast hero, Nikolai Tsiskaridze, who has darkish skin anyway, danced with an extensively bare midriff, his lilac trousers matched by a jeweled short-sleeved bikini top. One might put up with much if only the "Shades" scene was transcendent in any way: transcendence is what that's all about. The Bolshoi's had impressive features: a corps de ballet of 32 women doing the famous single-file entrance with legs in arabesque, all rising unusually high. But throughout the corps, there were different ideas about where the front arm should go, where the eyes should be directed and how the back should work. The scene became a technical feat without any serious classical poetry. |

|

|

| The main event of the first cast was the confirmation, as in "Le Corsaire," that the Bolshoi's beautiful prima Svetlana Zakharova is waking up as an artist of nuance and authority. Even so, she's at her least nuanced where she needs to be most, in the "Shades" scene. The same problem applies to the dignified, intelligent second-cast Svetlana Lunkina. Another junior whiz kid, Natalia Osipova, played the second heroine, Gamzatti. She has a prodigiously high jump and is mistress of all the arduous technical hurdles of the role. But her acting consists of making Gamzatti a coldly triumphant bitch, and her dancing tends to emphasize flash, often at the cost of shortening her phrases and giving her energy an impacted, ungenerous quality. "Ungenerous" is a word that is seldom applied to Bolshoi performers, and it didn't apply to Ms. Osipova last year in Mr. Ratmansky's "Jeu de Cartes." We are watching the Bolshoi in a state of change, but there is no predicting just what direction the change will take this sometimes most life-enhancing of ballet companies. Related |