Lo mejor para dos rebanadas de pan.

Dining & Wine | ||

| The Next Best Things in Sliced Bread By JULIA MOSKIN Published: April 30, 2008 | ||

Photographs by Hiroko Masuike for The New York Times Top, at Taim on Waverly Place lunch is a green falafel. At Little Morocco in Astoria, Queens, the merguez sausages with harissa, bottom, are a good bet. | ||

| NEW YORK has long been a city of stand-up eaters, but that doesn't mean people aren't picky. To make it here, a sandwich has to work overtime, being portable, filling, interesting and tasty. "What's better than a really great sandwich?" said Alexandra Raij, the chef at Tía Pol and El Quinto Pino, who is hosting a sandwich potluck for friends at her apartment next week. "Nothing that I've ever made." It should be noted that Ms. Raij is the inventor of several memorable sandwiches, including one filled with sea urchin and drizzled with fragrant mustard oil. But with all respect to her uni panini, it is not a real New York sandwich. Slim and precise, it lacks the compressed, complete pleasures of the Cuban sandwich, the heft and chew of a fully loaded gyro, the cool crunch of a Vietnamese banh mi. Those three are two-fisted, five-minute complete meals with the kind of flavor and texture contrast available on, say, a seven-course tasting menu at Jean Georges. A great New York sandwich is large; it contains multitudes. And new contenders are turning up all the time to challenge the mighty meatball parm and the elegant B.L.T. Whether invented, imported, or refined here whether discovered in the boroughs or farther afield the seven sandwiches here move the dialogue forward. The research for this article produced as much regret as revelation, with unrequitable longings for far-away creations like Chicago's jibarito (steak squeezed between thin, crusty slices of smashed plantain) and extinct species like the chacarero of Jackson Heights, Queens: a Chilean sandwich with a garnish of chopped green beans, the specialty of a bakery that is now closed. Most of all, the research was extremely filling. The ground rules: A sandwich had to be composed as such; mere food on bread did not count. (This left out, for example, pan de lomo saltado, a popular Peruvian stir-fry of beef, onions and peppers laced with soy sauce, typically served with French fries, but piled onto a crusty roll for sandwich purposes.) Burgers and wraps were out of the running, as was the universe of empanadas, samosas, patties and arepas; the same went for any sandwich that had to be eaten inside a restaurant or was otherwise unavailable for travel to a picnic, a ballgame or a playground.

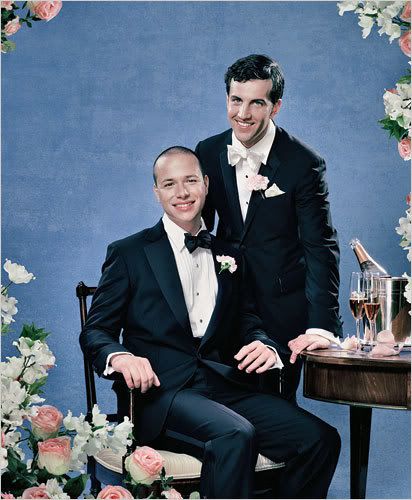

SANDWICH MERGUEZ AU HARISSA Magid Atif has worked almost every job in the restaurant business, starting as a busboy at the Purity diner in Brooklyn when he arrived from Casablanca in 1985. "Finally, I decided to go to cooking school, and I wanted to go to Paris but my funds would only allow me to go to Pittsburgh," he said last week in Little Morocco, the breezy cafe in Astoria, Queens, where he is now an owner and chef. Steinway Street south of the Grand Central Parkway is lined with hookah cafes, halal butchers, Middle Eastern bakeries and North African restaurants; a mosque across the street provides a steady stream of customers. Mr. Atif's time at the Cordon Bleu served him well, but eventually his cooking circled back to the spicy, paprika-reddened merguez sausages he said he learned to make from the Jewish butchers of Casablanca. The merguez are made daily at the cafe, cooked to order and stuffed into crusty, grilled "petit pain" "little bread" in Casablanca, a k a Italian rolls in Queens with cubes of cucumber and tomato, chopped green olives and a hot-pink, spicy, garlicky harissa, also made in-house. "I mastered it through many kitchens," he said. Wine vinegar and extra oil emulsify Mr. Atif's harissa into a tangy sandwich spread that takes a bow toward mayonnaise. | ||

Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times At Kiosko in Port Chester, N.Y., marinated pork goes from the grill to the bread. | ||

CEMITA POBLANA A cemita has the familiar look of a Big Mac until you bite into it. To absorb the layers of spicy meat, soft avocado, fluffy bread and the thick flesh of whole chili peppers is to leave the fast-food nation forever. "Poblano food is famous in all of Mexico," said Raúl Hernández, a restaurant worker who was polishing off a cemita at Los Girasoles in Woodside, Queens, last week. Pining for regional Mexican food used to be sad sport for food lovers in New York, until the city got lucky in the late 1990s with an influx of immigrants from the state of Puebla. (Many of the kitchen workers in the city's best restaurants are Poblano.) Papalo, a fresh herb with the bite of watercress and the breath of cilantro, gives lightness to a sandwich that can weigh a couple of pounds at the outset. "Without papalo it is not a cemita," said Tony Quintero, an owner of Kiosko, in Port Chester, N.Y., a once-neglected Westchester County town now revived as a destination for excellent, authentic Latin-American restaurants. Mr. Quintero's pork butt al pastor, marinated in citrus, chilies, cinnamon and cumin, then crisped on a griddle with shreds of pineapple, makes the best cemita around. Order it without the lettuce and tomatoes, concessions to American sandwich convention.

KNISH PRESS The owners of Press 195, a sandwich joint with stores in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and Bayside, Queens, may have avoided putting the word "panini" on the menu. Nonetheless their futures are staked to pressed sandwiches: they have more than 30 on the menu. "Every deli in New York has panini now," said an owner, Chris Evans, who grew up flipping burgers at the estimable Donovan's Pub. But what the delis don't have yet is the knish press: a sandwich built on a split potato knish, the brainchild of Brian Karp, the chef and co-owner. Squeezed in the hot press, the knish's crust becomes thick and crunchy, and the peppery, onion-tinged mashed potato inside melts into the filling. The pastrami version is thought-provoking, but even better is London broil with gobs of spicy brown mustard and an "onion jam" that takes you right back to the hot dog cart. The knishes are brought in daily from Gabila's in Coney Island. These square, deep-fried specimens are generally considered inauthentic by knish purists, who prefer them round and doughy, but this is an excellent use for them. "When we got to a certain level of production, Gabila's agreed to supply us fresh, not frozen," Mr. Evans said. "That was the day we felt like we made it." Order it well-done and be prepared to wait.

NIU ROU SHAO BING Those who consider China an unlikely source of handcrafted breads should consider the popular breakfast called you tiao shao bing: a fried cruller folded inside a fluffy sesame-sprinkled pancake, essentially a bread sandwich. In New York, shao bing (sesame pancakes) often appear at Beijing-style fried dumpling shops, known for their remarkable price-to-quality ratio and their lack of amenities, like chairs. But they also make niu rou shao bing, an exquisite sandwich on bread that rivals anything from Sullivan Street Bakery or Tom Cat Bakery. The flat-bottomed woks used to sear the dumplings are put to work frying shao bing the size of large pizzas. Right out of the wok they are sprinkled with sesame seeds, hacked into wedges, dabbed with hoisin sauce and stuffed with braised beef. The crunchy sandwich shows off the bread's flaky inside, subtle scallion flavor and golden crust. (The key is timing: wait for bread that is hot off the stove.) Kai Feng Fu Dumpling House in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, is one of the best of New York's new crowd of specialists in mian shi, meaning flour food, a staple of Northern China. "It's a way of categorizing dumplings, noodles and bread as opposed to rice, the staple of the South," said Fuchsia Dunlop, a British journalist who graduated from culinary school in Sichuan and has written books about cooking and eating in China. "They use a bit of yesterday's dough for leavening," she reported after quizzing the cooks at Kai Feng Fu in Mandarin last week. "The dough is pressed out, then they scatter it with chopped scallion, then fold and press it again." Her new memoir, "Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper," is about her serious effort to break through from eating as a foreigner in China both in her mouth and in her mind. "You would have to get to the point where a beef sandwich and a goose intestine were equally appealing," she said. "It takes time."

(Note: The sandwiches at the East 14th Street location of Vanessa's are not recommended.) | ||

Suzanne DeChillo/The New York Times Province in TriBeCa serves a fish sandwich like no other: spicy mackerel. | ||

| BENNY MAC One day last year at the Watchung Deli, at the request of a student from a nearby school, Ben Gualano piled mac-and-cheese onto a chicken cutlet sub with barbecue sauce and bacon, squeezed it shut somehow, and the Benny Mac was born. "Now the kids from Montclair High and the ones from M.K.A. are fighting over whose idea it was," one of the deli's owners, Gary Kiffer, said with satisfaction, referring to the local public and private schools. The Watchung, in business since 1926, has stayed true to the deli's German roots, producing endangered species like German cucumber salad, egg custard in little foil cups and macaroni and cheese from scratch every day. It also carries an ample stock of Tastykakes, including hard-to-find Butterscotch Krimpets. The Benny Mac may still be a work in progress, from a strictly epicurean point of view: the mac could be cheesier, the roll crunchier, the cutlet more flavorful. But it is more than a sandwich. It's a full-body experience like a mud bath, but with extra ooze. One taster said afterward, "There was bacon in there?"

CHILI MACKEREL MANTOU Province's crusty, spicy, resoundingly fishy mackerel mantou is nothing a fish sandwich might expect to be. Instead, it resembles a hot dog with the works: chewy, salty and squirting juice from the heap of crunchy pickled shallots on top of the fried fillet. Holding it all together are the steamed, fluffy buns known as mantou. "Growing up in Hong Kong, I ate everything with chopsticks in one hand and a mantou in the other," said Pak Wong, an owner. "It made sense to put the food and the bun together." Characteristic of Northern China, mantou are pillowy like English muffins, soft like hamburger buns, and they soak up flavors like nothing else. This sleek shop straddles chic TriBeCa and scrappy Chinatown, much like its sandwiches, which incorporate kimchi, braised pork belly, beef burgers and Japanese pickles. "Our sandwiches are very New York because they are not Chinese, not Korean, but all kinds of things we like," Mr. Wong said.

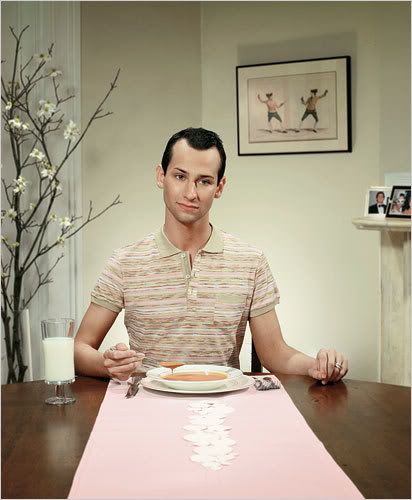

GREEN FALAFEL Working as a chef, Einat Admony sharpened her palate at Danube, Bolo and Tabla before turning her attention to her own "home food" in 2003. "There are a million falafels in New York, not to mention in Tel Aviv," she said, referring to the Israeli city where she grew up. But, she said, to make a great falafel sandwich, with its many components hot and cool, crunchy and soft, spicy and smooth is exacting. "It's all these small things that you taste and taste and taste every morning," she said. Taim's version is transformed by the fresh herbs that go into the dough: typically a golden mass of chickpeas but bright green here from quantities of cilantro, parsley and mint. That breath of fresh herbs, along with the crunch of the hot crust and the earthy cream of the tahini, pulls the Taim falafel to the front of the pack. "There is something about the taste here, like each thing has more flavor than it does anywhere else," said Anna Stojanowska, who lives in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, but journeys to the West Village for lunch sometimes. "There's actually a great falafel place at my subway stop in Brooklyn, but this one is just that little bit better, you know?"

| ||