Antiguedades Thai en problemas legales.

ART |

| Art Thai Antiquities, Resting Uneasily By JORI FINKEL Published: February 17, 2008 |

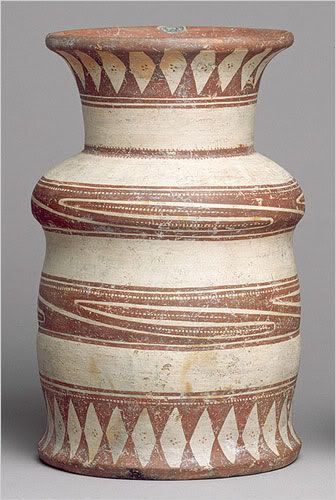

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art A ceramic pot |

| IT just might rank as one of the biggest accidental discoveries in archaeology. In the summer of 1966 a Harvard student named Steve Young was living in a village in the northeast reaches of Thailand, going door to door canvassing political opinion for his senior thesis, when he tripped over the root of a kapok tree. As he hit the ground he found himself face to face with some buried pots, their rims exposed by recent monsoons. Intrigued by the look and feel of the unglazed shards, he knew enough to bring them back to government officials in Bangkok. Works from Ban Chiang What he had stumbled upon is now viewed as one of the most important prehistoric settlements in the world. Initially dated as early as 4000 B.C. a date since revised amid much controversy to 2000 B.C. or even later the so-called Ban Chiang culture is the earliest known Bronze Age site in Southeast Asia, documenting the early development of culture, agriculture and technology to the region. |

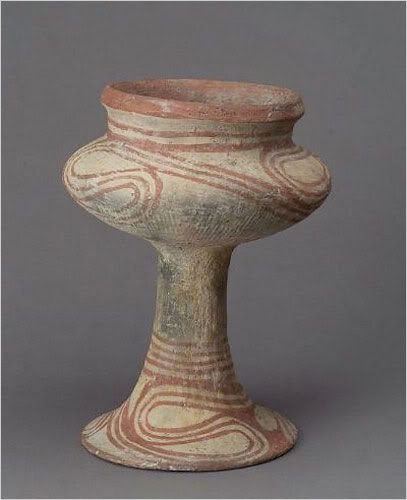

Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston A goblet made of stone |

Now Ban Chiang is in the news again as a result of a five-year undercover investigation by three federal agencies. Their examination centers on two Los Angeles antiquities dealers, Cari and Jonathan Markell, and a wholesaler, Bob Olson, who federal agents say donated Ban Chiang artifacts to museums at inflated values in a tax fraud scam. Last month four California museums the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Bowers Museum of Art in Santa Ana, the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena and the Mingei International Museum in San Diego were raided as part of the inquiry. The investigation could also have broad implications for other museums across the country. In the affidavits filed to obtain search warrants, the agents laid the groundwork for a legal argument that virtually all Ban Chiang material in the United States is stolen property. In essence, the paperwork states, antiquities that left Thailand after 1961, when the country enacted its antiquities law, could be considered stolen under American law. And since Ban Chiang material was not excavated until well after that date, practically all Ban Chiang material in the United States could qualify. |

Photo: Los Angeles County Museum A bracelet made of copper alloy |

| Among the many American museums with Ban Chiang artifacts are the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Cleveland Museum of Art; the Minneapolis Institute of Arts; and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. And that roster includes only institutions that have published highlights of their collections online. "I believe that virtually every big American art museum that collects Asian art has some Ban Chiang material," said Forrest McGill, chief curator at the Asian Art Museum. His museum owns 77 Ban Chiang objects, from painted earthenware bowls to bronze bracelets and stone ax heads. After learning of the federal investigation, he said, he reviewed these acquisitions almost all made before he arrived at the museum in 1997 for links to the Markells. He found none. |

Photo: The Minneapolis Institute of Arts An ear ornament made of glass |

| "We are nervous about everything been nervous, getting nervous," Mr. McGill said. "It's not as easy as you would think to be up to date and conversant with different countries' laws and to know which foreign laws the U.S. is committed to enforcing and which not." The Freer and Sackler have 56 works, mostly ceramic vessels. The Met has 33 pieces in its holdings, among them vessels, bronze bracelets, bells and ladles. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has 17, including gray stoneware pots and beakers and assorted clay rollers. The Cleveland Museum has eight artifacts, mainly jars. The Minneapolis Institute owns two ceramic jars and three glass ear ornaments. None of the acquisition records posted online mention the Markells or Mr. Olson. And for sheer volume of material, none of these museums approach the Bowers, which has roughly 1,000 artifacts. But the very specter of "looted goods" can prove a public relations nightmare for museums, which helps to explain why few curators contacted at those museums were willing to be interviewed about Ban Chiang artifacts. |

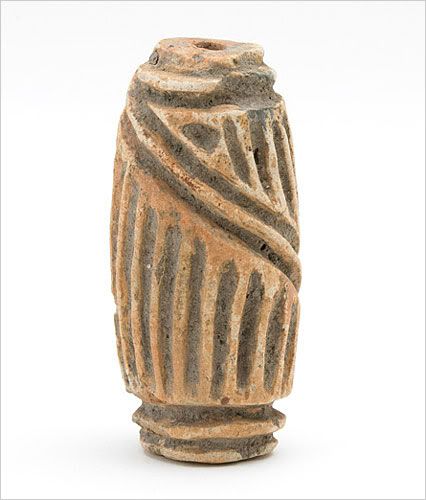

Photo: Freer Sackler Galleries A bead, cylinder stamp, or roller |

| Beyond public relations problems are the potential legal difficulties. In the most extreme example Marion True, a former antiquities curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, was indicted in Italy on charges of conspiring to acquire stolen objects for her museum. More generally United States case law on cultural patrimony is fast evolving, reflecting a growing awareness that collecting certain objects can encourage looting of archaeological sites. American museums have thus seen foreign laws that were long overlooked at home suddenly taken seriously. In the affidavits supporting the search warrants in the federal investigation, for example, agents invoke a 1961 Thai law, the Act on Ancient Monuments, Antiques, Objects of Art and National Museums, stating that "buried, concealed, or abandoned" objects are "state property" and cannot legally be removed from Thailand without an official license. They quote a Thai government official as saying that as far as he knew, Thailand's Department of Fine Arts "had never given a license to anyone to take antiquities out of Thailand for private sale." |

Photo: Los Angeles County Museum of Art An adze head made of metal with a copper alloy |

| Then, because a foreign country's law is not necessarily recognized in the United States, the affidavits cite two federal laws that could give the Thai statute some teeth, the National Stolen Property Act of 1948 and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979. Of course it's ultimately up to the courts, not federal agents, to determine what constitutes a violation of American law. And no indictments have been filed. But Patty Gerstenblith, a DePaul Universitylaw professor, said the affidavits signaled a serious federal interest in Ban Chiang as well as tax fraud. "I can't say it's going to be a slam dunk for the government if this reaches court, but I will say the information in those affidavits is impressive," she said. "It was, after all, a five-year investigation. We can as outside observers draw the conclusion that there is a fairly substantial likelihood that this Ban Chiang material could be considered stolen property under U.S. law." |

Photo: The Minneapolis Institute of Arts An ear ornament made of glass |

| The first major excavations of Ban Chiang began in 1974, led by the University of Pennsylvania in partnership with a Thai group. Joyce White, a scientist who now oversees the Ban Chiang project at the university's museum and is assisting the federal government with the current investigation, was a graduate student at the time. She remembers seeing crates of excavated material arriving at the university on loan from the Thai government. "There were what archaeologists call small finds bronze bracelets, clay rollers and so on," she said. "And then there were bags and bags and bags of broken pottery." (Some research material remains at the museum on long-term loan.) By the 1980s Ban Chiang material was flooding the international market. "I'm told that some 40,000 pots have come out of Ban Chiang, excavated from the site," said Mr. Young, the former Harvard student, in a telephone interview in which he confirmed the details of his discovery, down to the bruises from his fall. The son of a former American ambassador to Thailand, he said he never collected the work himself out of concern for his family's reputation and now owns only one pot, a gift from a Thai princess. Other collectors did amass the material, however, especially in the 1980s and '90s. The objects were abundant and, by comparison with other antiquities, cheap typically under $1,000. It was mainly during this time that leading American museums secured donations and, to a lesser extent, made acquisitions to help fill gaps in their Southeast Asian collections. |

Photo: Freer Sackler Galleries A bead, cylinder stamp, or roller |

| Museums have in the past argued that they were safeguarding objects already on the open market. But many archaeologists find the collecting of such artifacts distressing because it removes objects from their original, information-rich context. "It destroys the archaeological record," Ms. White said. "It's shameful really, a destruction of knowledge." Increasingly sensitized to those concerns, many museum curators now say they wouldn't touch the stuff even if offered by their most prestigious donors. "We would turn it down," said Robert Jacobsen, chairman of the Asian art department at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, "and not just because of the investigation in California, but because times have changed. There's a moral basis here." Asked whether his museum would consider repatriation, Mr. Jacobsen said: "When we acquired or were given these works, and I think I speak for all museums here, we did not think of them as illegal. But if it comes to pass that legislation declares this material illegal, we would simply return it." Mr. McGill in San Francisco also said he would take any claims "very seriously," while noting that the Thai government has never contacted him for the museum's Ban Chiang artifacts, despite a history of collaboration. "We did a big exhibition borrowed from Thailand two years ago," he noted, "and the director of the National Museum in Bangkok was at our museum several times." Still, he said, he is watching closely to see how the federal investigation unfolds. |

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art A beaker-shaped vessel |

| So are legal experts in cultural patrimony. Ms. Gerstenblith said the inquiry could lead to criminal trials or civil forfeiture proceedings. In the meantime she is urging all museums, "for ethical if not legal" reasons, to review their Ban Chiang objects. "When they accepted those donations, what kind of documentation did they ask for? Where did the pieces come from?" Stephen K. Urice, a professor at the University of Miami School of Law, said the legal issues were far from cut and dried. He pointed out that National Stolen Property Act of 1948 applies only to property valued above $5,000 and that federal courts had not yet upheld the application of Archaeological Resources Protection Act to foreign antiquities. He also cited a precedent established by a 2003 federal appellate court decision against the antiquities dealer Frederick Schultz, which puts a burden on the foreign government to show that it enforces its own property statute at home. |

Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston A bronze bracelet |

| Imagine "you have this vast body of archaeological material over which another government has waved its wand and said it's ours," Mr. Urice said, "but they have not done anything more than that to protect it. Under those circumstances, there is an open question as to whether the U.S. would treat it as stolen." As for the next steps in the federal investigation, Mr. Urice is not placing any bets. "The whole thing could be dropped altogether because of insufficient evidence or because they are feeling weak about their legal theories," he said, "or this could move forward into an important, precedent-setting case." |

Multimedia- Slideshow |