Para los gourmets, Cartagena se hace presente. /New York Times.

TRAVEL |

| For Foodies, Cartagena Is Now on the Map By DANIELLE PERGAMENT Published: October 26, 2008 |

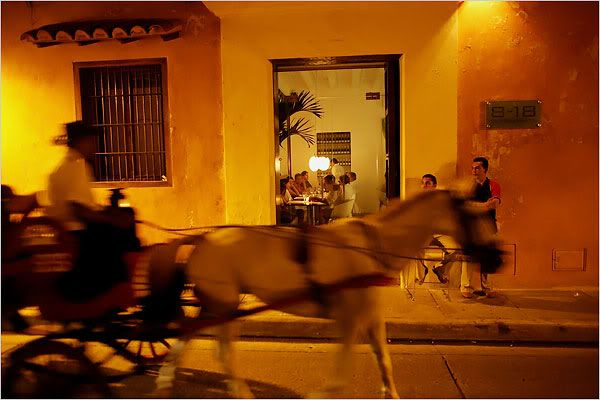

While the rest of the world was looking the other way, the port town of Cartagena cultivated its own taste. Menus are sprinkled with freshly caught fish, bright vegetables and pungent spices, like cumin and coriander. A carriage passes La Vitrola, left, the culinary kingpin of Cartagena. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| GREAT food cities tend to have a few things in common a history steeped in culinary arts, a bounty of exceptional ingredients and a handful of cocky young chefs at the helm. A history of cocaine trade, drug violence and rotting neighborhoods don't usually make the list. But recently, the Colombian port town of Cartagena has become an unlikely food destination, attracting the kind of culinary travelers who spend their vacations in Rome and Paris. And what they find is a city far more exotic, but no less adroit at catering to sophisticated palates 200-year-old Spanish colonial mansions refurbished with crisp interiors, trendy bistros that elevate plantains to haute fare, and theatrical rooms buzzing with dignitaries in starched collars and Windsor knots sipping minty rum drinks. "Colombian food has been hiding," said Felipe Arboleda, the boyish, perpetually smiling former chef at Palma, one of the city's white-hot restaurants. "Colombians hide their identities when they travel because people think we're all drug dealers. People ask if I have a cocaine plantation or if I am related to Pablo Escobar. So our cuisine hasn't left the country." Inside the borders, it's a different story. While the rest of the world was looking the other way, Cartagena cultivated its own taste. Menus are sprinkled with bright vegetables and pungent spices, like cumin and coriander. With the Caribbean warming its shores, fish is abundant and the house specialty is always freshly caught something, rubbed with the fiery flavors so celebrated in this corner of the world. Occasionally, the chef may give a nod to French or Italian cooking, but tamarillo ratatouille, grilled squid and homemade coconut broth are never far away. "This country is not just about drugs," Mr. Arboleda said. "Soon, it will be about the food. You'll see." |

La Vitrola's kitchen. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| La Vitrola To exhaust the metaphor, La Vitrola (Calle de Baloco No. 2-01; 57-5-660-07-11) is the culinary kingpin of Cartagena. Part jazz club, part lounge, part highly touted restaurant, La Vitrola channels old Havana whirring ceiling fans, swaying palm fronds, slatted window shutters that throw the light just so. Put another way, best of luck getting a table. Surprisingly, when I called this summer, I was able to get a reservation for 9 p.m. the next day. But even more surprisingly, my friends and I were turned away when we arrived: no more tables. The manager, sweating and apologizing profusely, insisted that we come back later for cake and Champagne on the house. So two hours later, after dinner at a bland bistro nearby, dessert was served: gooey chocolate cake, crisp buttery cookies and cold Veuve Clicquot, all paid for by the manager's conscience. Meanwhile, a six-person jazz band was warming up, drunk and happy patrons were pushing tables aside, and the house mojitos, true to their purpose, made friends and dancers of everyone neighbors, dignitaries, tourists and staff members alike until early morning. |

Part jazz club, part lounge, part highly touted restaurant, La Vitrola channels old Havana. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| It wasn't until the next day that I tasted the food (go for lunch when it's less crowded). The menu is built around seafood with a kick. Normally, I'm suspicious of fish camouflaged in spices, but the red snapper à la diabla with feverishly hot chili sauce, was so fresh I could still taste the salt water. Having lunch with three other people has the bonus of tasting half the menu: grilled salmon rubbed with tangy lemon and lime zest; seared tuna sweetened with mango chutney and honey; sea bass amped up with jalapeño and zucchini salsa; and warm ravioli in a light tomato broth with chunks of fresh lobster meat inside. Lunch came to about 30,000 Colombian pesos a person, about $12, at 2,335 pesos to the dollar. We washed down the entire cast of "Finding Nemo" with a pitcher of icy white sangria with coarse slices of green apples bobbing inside. By the time we were handed the dessert menu, we had come full circle. It would have been easy to spend the rest of the trip at La Vitrola, but it was time to move on. |

The menu at La Vitrola is built around seafood -- with a kick. Garlic shrimp, left, in a white wine sauce tops fried plantains. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| Palma (Calle del Curato No. 38-137; 57-5-660-27-96) opened its doors two years ago in one of the prettiest corners of the Old City, opposite the venerable Hotel Santa Clara and nestled between blocks of Crayola-colored houses. Inside, however, it was Cartagena meets South Beach: black and white and stark all over. Double-height ceilings, a glassed-in courtyard and a roof deck overlooking the neighborhood everything to suggest that the designer was paid more than the chef. The waiter brought over a basket of warm, fried plantain patties with a cool yogurt dipping sauce, a nod to the street food of Cartagena and a reminder that though we may not be on an island, this is still the Caribbean. I'd like to say that one basket was enough, but we went through wait for it three. We devoured the salty, crispy plantain cakes like ravenous backpackers. I could have almost forgone dinner, but the serving staff started to look at us in a funny way. |

The menu at 8-18 is Colombian by way of Spain. It's been three years since the restaurant had its celebratory opening, but 8-18 still rises to the hype. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| Palma's menu is part Italian and part Colombian, which partly works and partly doesn't. The mozzarella salad was as sad and bland as it was colorless. But its memory evaporated when I moved on to the specialty of the house: paper-thin sea bass carpaccio topped with a fresh mango sauce speckled with chopped cilantro, tomato, dill and corn. It tasted (dorky, but true) like the tropics: sweet and green and faintly briny. Next came the pappardelle al teléfono, ribbons of pasta in a light pink sauce with fresh chunks of tomato, basil and drizzled with olive oil. It was comfort food Italian style, expertly al dente in a sauce dense with the rich taste of tomatoes and the lush texture of cream. The whole meal came to 30,000 Colombian pesos. The price seemed especially reasonable considering we had spent about four hours continuously drinking, nibbling and sopping up any remains with warm focaccia. |

A plate of fresh ceviche -- grouper, prawn, and octopus -- delicately marinated in lime juice, cilantro and local herbs (24,000 pesos) at 8-18. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| 8-18 The word on 8-18 (Calle Gastelbondo No. 8-18; 57-5-664-61-22) was that it had come through its celebratory opening three years ago with its culinary edge intact. But there were rumblings that the kitchen had slid once the spotlight moved on. We went to settle the dispute. |

Eight-18's decor is white, white, white with accents of green. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| Eight-18 shares its aesthetic sensibility with Palma white, white, white with accents of green. Photographs of leaves blown up to the size of small cars, decorative reeds resting on every dinner napkin and glass marbles inexplicably strewn across the tables. For my money, it was a little contrived. The menu at 8-18 is Colombian by way of Spain. The appetizer page was too lengthy to settle on just one dish, so we started with a small dome of fresh octopus carpaccio dressed with spicy, chili- infused olive oil and fresh coriander (21,000 pesos). That was followed by a round of caught-that-morning ceviche grouper, prawn, and octopus delicately marinated in lime juice, cilantro and local herbs (24,000 pesos). |

Fresh octopus carpaccio dressed with spicy, chili-infused olive oil and fresh coriander (21,000 pesos) at 8-18. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| The appetizers kept flowing. We followed all that rawness with seared scallops tossed with parsley and lemon juice (24,000 pesos), warm mussels with crispy mixed greens (20,000) and Coco 8-18, a creamy fish soup thick with shrimp, cabbage, green onions and coconut milk (24,000). The main courses sat patiently on their page. But after working our way through the airy and citrusy appetizers so well suited for the climate of Cartagena the idea of beef loin with mushroom ragù and potato purée was as appealing as a winter coat. Instead, we ended the meal as we started it: with cold, minty, palate-cleansing mojitos which, matched the décor seamlessly and pronounced that 8-18 still rises to the hype. |

Located outside the Old City, in the neighborhood of Barrio Getsemaní, the restaurant Oh! Lá Lá serves as close to a perfect meal as can be found. The chef and owner, Gilles Dupart, left, runs the restaurant with his wife and cooks up meals like tomato confit and baked sea bass with creamy Parmesan risotto. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| Oh! Lá Lá ... Despite the zealously punctuated name, Oh! Lá Lá ... was subdued, relaxed, and as close to a perfect meal as I found. For starters, it was outside the Old City, in the neighborhood of Barrio Getsemaní. As pretty as it is, the old quarter throbs with tourists, street vendors and skeletal horses pulling carriages at full speed. Leaving the walled city felt great. I highly recommend it. Then there's the décor. Oh! Lá Lá ... (Calle 25 No. 9A; 57-5-660-17-57) is so cute you'll think you've died and gone to a French dollhouse. The entire place consists of six tables, a bar that fits two stools and a kitchen the size of Barbie's Dream House, all wrapped up in soft orange walls. As soon as we sat down, the Ding! Ding! Ding! moment: "Our food takes time to prepare," said our waitress, Carolina Vélez, who owns the restaurant with her French husband and chef, Gilles Dupart. "We like to say it tells a story." |

The décor at Oh! Lá Lá is so cute you'll think you've died and gone to a French dollhouse. The entire place consists of six tables, a bar that fits two stools and a kitchen the size of Barbie's Dream House, all wrapped up in soft orange walls. Carolina Vélez, co-owner, left, doubles as a waitress. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| Think of the menu, Ms. Vélez suggested, as a rough outline. Her husband would happily accommodate special orders, half orders or meatless orders. "In Cartagena, we don't always have every ingredient," she said. "We must modify. Our dishes come with the freshest ingredients of the day." They also come with a side of biography. I started with the warm lentil soup (8,000 pesos) served with thick, crusty bread for dipping. "I like it without the chorizo," Ms. Vélez said, adding that she was raised a strict vegetarian. Next was the tomato confit (8,000 pesos) juicy oven-roasted plum tomatoes and caramelized onions layered over a flaky crust and drizzled with basil-infused olive oil "a recipe we picked up living in Paris." Then Ms. Vélez steered us off the menu for an impromptu plate of artisanal Sardinian cheeses hard and soft varieties ranging from sharp and spicy to grassy and earthy, with mesclun greens (9,000 pesos). Another pause for gastronomical biography: "This cheese reminds me of the summer I lived in Corsica," she said. "You can taste the white flowers." |

A blackened halibut steak at Palma, which has a menu that's part Italian and part Colombian. Photo: Scott Dalton for The New York Times |

| Maybe food tastes better when it comes with a story, or maybe it was the sauvignon blanc, but by the time the baked sea bass arrived, paired with a creamy Parmesan risotto, I was nearly misty eyed at my (completely fabricated and utterly untrue) memory of watching fishermen cast their nets in the morning light. Dessert, Ms. Vélez warned, was her husband's chef-d'oeuvre. We tried to protest, but the kitchen could not be stopped. Next thing I knew, I was staring at a warm apple crumble swirled with vanilla sauce (6,000 pesos): gooey, crunchy and delicately sweetened with cinnamon. Ms. Vélez looked pleased. This was a woman who clearly believed in happy endings. |

| |

| |