Arte Marcial Tibetano

Art Review |

| In War and Peace, in Silver and Gold By KAREN ROSENBERG Published: January 4, 2008 |

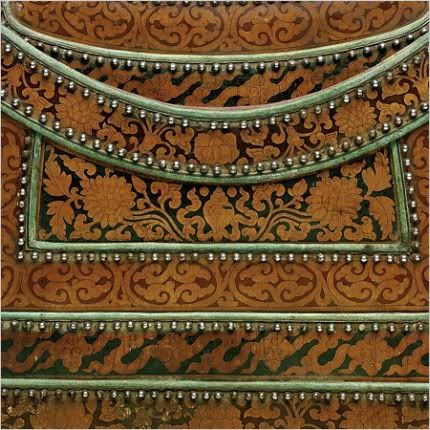

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art Detail of a breast defense from a horse armor, Tibetan or Mongolian, 15th to 17th century. |

| Tibetan Buddhism, represented by the peace-loving Dalai Lama, is not normally seen as a religion that advocates violence. Earlier generations of followers, however, defended the road to enlightenment with armed horsemen. Tibetan Arms and Armor at the Met Beginning in the seventh century Tibetan Buddhists outfitted their gods as well as their warriors. In ancient Himalayan paintings, deities brandish weapons, including the Sword of Wisdom, in defense of religious doctrines. They also wear protective battle gear, as in the case of the eighth-to-ninth-century figure Tsenpo, described in an ancient manuscript as "a god who became the sovereign of men, due to his power derived from the great radiance of his sacred helmet." |

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art "Sword" (detail) Tibetan or Chinese, from the 14th-16th century. |

This paradox of militant Buddhism inspired the Metropolitan Museum of Art's fascinating 2006 exhibition "Warriors of the Himalayas: Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet," which presented some 130 examples of military art. Donald LaRocca, the museum's arms and armor curator, has created a follow-up installation of 35 objects from the Metropolitan's collection (including five acquired in 2007), which opened in mid-December in the Arthur Ochs Sulzberger gallery. (Mr. Sulzberger, chairman emeritus of The New York Times Company, is a former chairman of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.) This time, in "Tibetan Arms and Armor," the focus is on defense rather than offense: examples of horse and body armor, dating from the 15th through the 20th centuries, outnumber swords, guns and spears. Most of these objects have seen more ceremonial than military action, despite Tibet's long history of military involvement with India, Mongolia and China (its current ruler). All of them equate supreme craftsmanship with defense of the body and Buddhist principles. A mannequin representing an armored cavalryman shows how the typical Tibetan warrior, from the 17th century on, dressed for combat. Over a mail shirt he wore a set of iron discs known as the "four mirrors," protecting the front, back and sides of his torso. He carried a bow case and quiver, a matchlock musket and a spear. On his head was a domed helmet that came to a point at the top. |

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art A Tibetan bridle from the 15th-17th century. |

| The exhibition includes seven of these helmets, which vary in age, construction and decoration. Some are made of segmented metal plates, while others have smooth, richly patterned surfaces. The oldest of the helmets on view has eight plates and a plume finial and dates from the 8th to the 10th century. The rarest is a one-piece bowl ornamented, in gold, silver and turquoise, with a Buddhist motif known as the Three Jewels. It was likely worn by a Mongolian follower of Tibetan Buddhism sometime from the 14th to 17th century. Another helmet, of Mongolian origin, is so heavy with text and imagery that one imagines the wearer collapsing under the spiritual weight. Encircling the conical form are inscriptions offering protection from bad planets and stars, destructive demons, weapons, harmful ghosts and a host of other threats. |

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art A Mongolian helmet from the 15th-17th century. |

| Horses were as lavishly and thoroughly equipped as soldiers, to judge from the variety and intricacy of the saddles, bridles, shaffrons (head guards) and stirrups on view. The Tibetans, in the tradition of steppe horsemen, continued to use horse armor long after it went out of fashion in the West. One iron and leather damascened (decorated with gold and silver) shaffron is among the most striking objects in the arms and armor galleries. Dating from the 15th to 17th century, it is thought to have been owned by a king or high-ranking general. Delicate scrolls adorn the area above the eyeholes, which are outlined with tiny iron spheres. A long strip of textured metal extends from snout to mane, bulging into a disc in the center of the forehead. |

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art A head guard, Tibetan or Mongolian, from the 15th-17th century. |

| Next to the shaffron a pair of exquisite leather neck defenses from the same period are painted with rows of gold lotus and peony blossoms. Pinned to the back of a display case, they resemble angels' wings from a medieval icon painting but are sturdy enough to function as armor. Similarly involved techniques were used in the making of stirrups, saddles and bridles. The Met's display includes a pair of stirrups with sloping dragon heads on the arch and a tread damascened with the motif of the Wheel of Law. On the underside are spirals, concentric circles and a lotus-leaf pattern. |

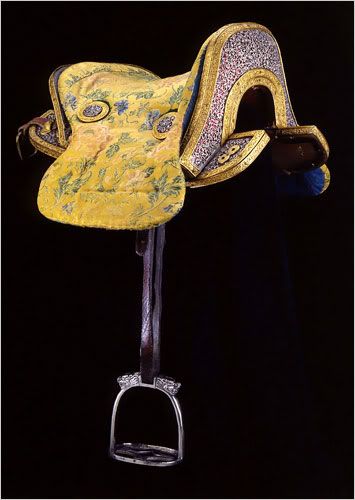

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art An Eastern Tibetan saddle and stirrup. |

| One exceptionally well-preserved saddle appears to have been made in China for the Tibetan market, during the 17th or 18th century. Its original seat cover, of silk embroidered with dragons, and the form of its gold-foil pommel plate resemble features of saddles made in imperial Chinese workshops. The underside of the saddletree, however, has been branded with the Tibetan letter "ka." The most riveting of the new acquisitions is a war mask, in iron trimmed with copper, thought to have been made sometime from the 12th to 14th century. Unlike the many surviving examples of ceremonial papier-mâché, leather and gilt copper masks, it was meant to be used in battle. Its fearsome scowl resembles the expressions of Japanese samurai masks meant to intimidate the opponent (which can be seen in the adjoining galleries of Ottoman, Chinese and Japanese arms and armor). |

Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art A war mask, Mongolian or Tibetan, from the 12th-14th century. |

| Unlike most of the other peoples represented in the Metropolitan's arms and armor galleries, Tibetans continued to wear their armor into the 20th century. As recently as the 1940s they wore traditional arms and armor at events like the Great Prayer Festival in the capital city of Lhasa. At this annual event government officials engaged in contests of skill with the spear, bow and arrow, and matchlock musket a case of Buddhism's war of art running parallel to the art of war. "Tibetan Arms and Armor From the Permanent Collection" continues through the fall of 2009 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, (212) 535-7710 . |

Multimedia SlideShow Tibetan Arms and Armor at the Met |