Alto en el MIO.

caught my eye surfing.....

World Arts. | |||

| Putin's Last Realm to Conquer: Russian Culture By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN Published: December 1, 2007 | |||

|

| |||

| MOSCOW The fight is long over here for authority over the security services, the oil business, mass media and pretty much all the levers of government. Vladimir Putin's Kremlin, notwithstanding some recent anti-government protests, has won those wars, hands down, and promises to consolidate its position in parliamentary elections. But now there is concern that the Kremlin is setting its sights on Russian culture. Just a few weeks ago, the Russian culture minister censored a state-sponsored show of Russian contemporary art in Paris. Criminal charges have been pressed during the last couple of years against at least half a dozen cultural nonconformists. A gallery owner, a rabble-rouser specializing in art that tweaks the increasingly powerful Orthodox Church and also the Kremlin, was severely beaten by thugs last year. Authorities haven't charged anyone. At the same time, the Kremlin is courting some big-name cultural figures like Nikita Mikhalkov, the once-pampered enfant terrible filmmaker of Soviet days, today a big promoter of Mr. Putin. There are signs of a backlash. In late October, a television debate program pitted Viktor Yerofeyev, a prominent Russian author, against Mr. Mikhalkov, who with a few others wrote a fawning letter, supposedly in the name of tens of thousands of artists, asking the president to stay in power beyond the constitutional limit of his term in March. "Have you heard of cult of personality?" Mr. Yerofeyev asked him. Mr. Mikhalkov fumbled. Mr. Yerofeyev won the program's call-in vote by a large margin, an event almost unheard of on today's Kremlin-controlled television. If you can call any television debate show a touchstone in recent Russian cultural history, that was certainly it. The show's rating went through the roof. Dozens of writers and artists signed petitions lambasting Mr. Mikhalkov for presuming to speak for them. A battle line over culture had clearly been drawn. These are not Soviet times, it's worth remembering, and artists, actors, filmmakers and writers here can do and say nearly whatever they want without fear of being shipped off to a gulag. Stepan Morozov and Aleksei Rozin, who play Michael Bakunin, the 19th century anarchist, and Nicholas Ogarev, the poet, in the Russian production of Tom Stoppard's "Coast of Utopia," were backstage one recent night extolling how free and lively Russian theater was. Theoretically, so long as the center of power remains unaffected, anything is allowed on the margins, where serious culture mostly operates (Russian pop culture seems not to ruffle any feathers, or maybe it doesn't want to, and television is firmly under the Kremlin's thumb). Even so, some prominent artists and writers, cognizant of a long, dark history of repression that Russians know only too well, and especially wary of the grip the church is gaining on the state, have been expressing deep anxiety about the government's starting to encroach on artistic freedom the way it has taken on other aspects of society. "They're creating, quickly, a kind of Iran situation, a new-old civilization, an Orthodox civilization," Mr. Yerofeyev said at his apartment the other evening, from inside the classic thick plume of cigarette smoke that still seems to engulf every Russian intellectual. "The climate has totally changed. What was allowed the day before yesterday now is dangerous. They don't repress like the Soviets yet, but give them two years, they will find the way. That call-in vote was a shock to the authorities, who thought everything was stable and prepared for the elections." Well, Iran's clearly over the top, but Mr. Yerofeyev is not alone in expressing fear. "Our future is becoming our past," the well-known novelist Vladimir Sorokin told me. His books, a few years ago, were destroyed and stuffed into a big papier-mâché toilet bowl devised by some ultra-nationalist youth groups. Mr. Sorokin's most recent novel foretells a Russia that has fallen into an ancient state of authoritarian rule. "We are returning to Ivan the Terrible's era," he predicted, speaking about the church and the general inward-turning, anti-Westernism afoot. Mr. Mikhalkov, on the set of his next movie, which is a military base outside Moscow, responded to these predictions with disdain: "Listen to what's on television and radio now and tell me, what limitations do you see?" He tried not to look exasperated. Artists are perfectly free, he said. "My view is simply that the modus operandi of Russia is enlightened conservatism," meaning hierarchical, religion-soaked, tradition-loving. That's certainly the official line. Then again, it's said that Russia has never dealt with its past the way Germany has, and indeed when the Kremlin culture minister tried to halt the exhibition of contemporary Russian art in Paris this fall, calling what he considered the offending works in it a "disgrace" to Russia, he was just echoing old-school Soviet rhetoric and bringing exactly that onto the country, disgrace. The show opened anyway (apparently some high-level French government intervention saved the day), but not before dozens of works were pulled, including one, "Era of Mercy," by the Blue Noses group showing two Russian policemen kissing in a birch grove. | |||

|

| |||

| The picture tells you how tepid the art is that can provoke a reaction here; it surely wouldn't make the slightest stir in an art gallery in the West. But then, context is everything. Quality hardly ever matters in these affairs. What caused an uproar with Roman Catholics and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani in the "Sensation" show at the Brooklyn Museum some years back wasn't great art, but its calculated mix of religion and pornography (and elephant dung) had the desired effect, and the same holds true here: politics, religion and sex, the Molotov cocktail of censorship, are also the topics over which Russia's cultural battle is being fought. It's the culture wars we all know, but in a country with a legal system that's notoriously ineffectual, if not corrupt. The Paris show's curator, Andrei Yerofeyev, Viktor's brother, now faces criminal charges, initiated by a vice speaker of Parliament, by pro-Kremlin youth groups and by members of the church. Charges have also been brought in recent months against Yuri Samodurov, the head of the Sakharov Center, the civil rights organization and museum, for showing some of the same art (the charge is essentially for hate speech). As in all culture wars, there's a dose of farce, too: Mr. Yerofeyev's boss, Valentin Rodionov, the director at the state-run Tretyakov Gallery, apparently embarrassed for having so obediently gone along with the censorship, has now sued the culture minister, Aleksandr Sokolov. Rumors are flying about the possible financial motives of those who benefit from all the controversy connected to what's censored. This is Russia, after all, where money has itself become an ideology, and, of course, we're also talking about the art world. Still, it's not a little shocking that no Russian artists in the Paris show protested when works were removed. "I don't think the art community in Russia is organized enough to protect its own interests," Mr. Yerofeyev remarked. He looked, not surprisingly, crestfallen. Complacency, self-interest and fear are sometimes hard to distinguish in these circumstances. Marat Guelman was a Putin ally and a political operative who has since turned critical of the Kremlin. When a gang of men came into his art gallery last fall and beat him, he was exhibiting the work of an ethnic Georgian artist. Russia and Georgia were then in a major spat over Georgia's arrest of Russian military officers on spying charges. The Kremlin was expelling hundreds of Georgians. Mr. Guelman doesn't know exactly who was trying to send him and perhaps others like him a message by his beating. As he has phrased it, "power has many different hands in Russia": the Kremlin doesn't have to issue direct orders for its many allies, religious, nationalistic and otherwise, to act in what they believe, rightly or not, to be its behalf. At the very least, though, he thinks it shouldn't be hard to find the criminals if the authorities want to. "The anti-Western hysteria rising in Russia has now impacted on the arts and, of course, the main role in this is played by the church," Mr. Guelman said. "Russian art is ironical. That's our tradition. And that's what both this government and the church don't like." He spoke in his apartment, which happens to have a great picture-window view onto a symbol of the resurgent church, the newly rebuilt Christ the Savior Cathedral, the one that Stalin notoriously blew up. Mr. Mikhalkov, on the military base outside town, was directing a sequel to his Oscar-winning "Burnt by the Sun" the other day. He was surrounded by actors in Soviet uniforms stomping their feet against the freezing cold in deep trenches dug into a vast, lonely snow-covered field. The sky was leaden gray. Aside from the Putin re-election letter, Mr. Mikhalkov has raised eyebrows lately by filming a pro-Putin election advertisement, and he produced a gushing birthday tribute to the president, which was shown on state-run television. He retreated to a trailer to hash over the debate, which, even as someone who loves attention as much as power, obviously continued to gall him. "Why are people frightened of patriotism?" he asked. He wanted to differentiate it from xenophobia. "There's a lot of worrying among the intelligentsia about teaching the basics of Orthodox culture. It's a hysteria." Russia needs authority, he said. "Maybe for the so-called civilized world this sounds like nonsense. But chaos in Russia is a catastrophe for everyone. Even if Putin isn't always the most democratic, he should nevertheless remain in power because we don't know that the new president won't begin by undoing what Putin has done." When I mentioned this remark to Alexander Gelman, a high-profile playwright during the perestroika days, he shook his head. "In the Soviet era there was only one party but there were plays and books that supported the idea of democracy, " he recalled. Despite the different spelling, he is the art dealer's father, so not exactly unbiased. That said, he made a good point: "The less democracy, the more cultural figures matter. If the tendency against democracy continues, cultural figures will gain more influence. "It's a disgrace for Russia that writers would replace political parties," he added. "But maybe that is what will have to happen." | |||

|

| |||

| |||

World Business. | |

| Venezuela's Fateful Choice By JENS ERIK GOULD Published: November 30, 2007 | |

|

| |

| | |

| CARACAS, Venezuela, Nov. 29 As petrodollars stream into oil-producing countries, Western officials have begun to demand greater accountability for how they are spent. Some countries known for corruption, like Nigeria and Azerbaijan, have heeded the call, increasing their financial transparency, or at least paying lip service to it. But Venezuela under the leadership of President Hugo Chávez appears headed in the opposite direction. "We see Venezuela on the other side of the road," said Mercedes de Freitas, executive director of Transparency International here. The group, which tries to combat corruption worldwide, ranks Venezuela as the least transparent country in Latin America and 162 out of 179 nations globally. And that could soon fall even lower. On Sunday, Venezuelans will vote on constitutional changes that would, among other things, grant Mr. Chávez unparalleled power to run the country's finances as he sees fit. If the referendum is approved, government accounting is expected to become still harder to fathom, and foreign businesses, many of them already afraid to invest, will find Venezuela even more forbidding. Already, Mr. Chávez's government is putting large amounts of oil revenue into development funds and state-owned companies that operate outside the official budget and are not subject to audits or legislative approval. The Fund for National Development, a leading fund of this sort, has received more than $30 billion since 2005 without regularly disclosing its balance, the progress of projects it finances, the whereabouts of billions of dollars it invests in bonds, or how often it receives revenue injections from the state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela. Under the proposed changes, Mr. Chávez seeks to formally strip the central bank of its autonomy, giving him the power to dictate monetary policy and the spending of excess foreign-currency reserves. Another measure would eliminate an already neglected rainy-day fund. Opinion polls released in the last week have found Mr. Chávez's proposals tied or trailing the opposition position among likely voters, after months of polls showing it likely to pass. In recent weeks, students have rallied in Caracas to protest the changes, and some of those demonstrations have turned violent. On Thursday, tens of thousands of people flooded the streets of the capital in opposition to the referendum proposals. Venezuela's foreign minister, Nicolás Maduro, asserted on Wednesday that a United States Embassy official was conspiring to defeat the referendum proposals, and threatened to expel the diplomat. And Mr. Chávez said this week that CNN was trying to instigate his assassination. Like this sort of political volatility, reduced access to information on public finances is expected to make investing in Venezuela a riskier prospect, said Francisco Rodríguez, who teaches economics and Latin American studies at Wesleyan University. Investors in Venezuelan bonds already struggle to ascertain what assets back the country's debt and what resources it could count on in the event of a financial crisis. Oil profits are the basis of Mr. Chávez's intended socialist revolution, which aims to help the poor in Venezuela and other countries. Petrodollars finance social benefits including free health care, free education and government-subsidized food, and oil profits permit the vast public spending that has helped create nearly four years of economic growth. But large chunks of revenue have been managed opaquely to a degree that it is hard to measure the state's success in carrying out its social projects or in monitoring corruption. "It's not really clear how the money is invested," said Theresa Paiz-Fredel, a senior director of Fitch Ratings. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, a program started by the British government with support from the World Bank, says that a lack of clarity in oil-revenue management can be a sign of the "resource curse," where natural resources fuel corruption and undermine the rule of law instead of contributing to long-term growth. Venezuela is not one of the 15 signers of the initiative, and some economists say it is laboring under the curse. They point to corruption charges this year against the state oil company, leveled by a pro-Chávez lawmaker. Officials denied wrongdoing, but eventually conceded that the oil company had too few rigs. Separately, a director of Petróleos de Venezuela resigned after a shadowy incident involving company executives, a charter flight to Buenos Aires with a Venezuelan businessman, and a briefcase with $800,000 in cash. Facing mounting criticism, Finance Minister Rodrigo Cabezas has released two reports this year disclosing the Fund for National Development's revenue balance, and he promised in May to conduct a comprehensive audit of all projects the fund financed to give it "more transparency." But analysts trying to gain access to the data are still frustrated, saying that the reports are neither detailed nor frequent enough. The New York Times requested interviews to obtain details on the fund from the finance ministry, the central bank, Petróleos de Venezuela and the state-run Banco del Tesoro. After more than two months of efforts, none of those organizations granted an interview or provided any information. | |

|

| |

| | |

| Simón Escalona, vice president of the National Assembly's finance commission, said he had not "seen any lack of transparency" in the development fund. But, Mr. Escalona was unable to provide updated information on its total assets, bond investments or on transfers from the state oil company to the fund. Mr. Chávez has long sought control over Venezuela's foreign reserves. The central bank has already lost much of its independence; a report in March by Barclays Capital said transfers from the bank to the Fund for National Development were determined more by Mr. Chávez than the bank. Still, the central bankers occasionally criticize government policy, a practice likely to end if the referendum passes, as will most public debate on state spending, Mr. Rodríguez of Wesleyan said. And the unfettered spending of reserves could increase inflation, at 17 percent already the highest in Latin America. "They will stop being foreign reserves," Mr. Rodríguez said, and become just "another account." In October, Fitch Ratings lowered Venezuela's outlook to negative from stable, saying that inflation and a weakening currency had made it vulnerable to a decrease in oil prices. Still, oil-producing countries are not generally known for their transparency. Qatar, for instance, does not publish figures for its large investment fund, which is fed by oil revenue, according to Luc Marchand, an analyst at Standard & Poor's. But even Russia, despite criticism that the government is weakening institutions, is adopting a system used by Norway that will integrate its main oil fund into the budget and make it easier to track, according to Frank Gill, also of Standard & Poor's. And authorities in Moscow have strict investment criteria for the oil fund. Venezuela differs from Russia and many petrostates, including Nigeria, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, in another way. Those countries all run budget surpluses, while Venezuela's heavy social spending results in a deficit, according to data compiled by Mr. Marchand. Some economists, like Mark Weisbrot at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, say that social spending, which he puts at 21 percent of the gross domestic product last year, is proof that Mr. Chávez is combating the resource curse. Mr. Weisbrot points to government statistics showing that poverty has fallen to nearly 30 percent from 44 percent since Mr. Chávez was elected nine years ago, and unemployment has dropped to 8 percent from 15 percent. Mr. Chávez frames his designs on full control of oil revenue as part of a crusade against Washington-based institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which he says advance American business interests. A deputy finance minister, Rafael Isea, told state television last summer that eliminating the central bank's autonomy would curb the I.M.F.'s ability to "manage our reserves and influence internal policies." The government has nationalized electric and phone companies here that once had American companies as stockholders, has ceased filing financial reports of the state oil company to the Securities and Exchange Commission, and has announced plans to withdraw Venezuela from the I.M.F. and the World Bank. In September, Mr. Chávez ordered the oil company to convert its investment accounts from dollars to euros and Asian currencies. The march to socialism has not been as smooth as he may have hoped. Officials became aware that plans to leave the I.M.F. could conceivably result in a default of Venezuelan debt. Months after the announcement, the country is still part of the I.M.F. Students of history warn that the 1970s oil boom also coincided with heavy spending and questionable accountability. In his book "The Magical State," Fernando Coronil, a professor of history and anthropology at the University of Michigan, documents how policies intended to spur development in the 1970s loaded Venezuela with debt and helped create financial crisis in the 1980s and '90s. "It's one thing to declare the intent to use these resources for the benefit of the population, it's another to prove it," he said, "and in order to do that you have to have checks and balances." | |

| |

Fashion & Style | |

| A Cover Girl Who's Simply Himself By GUY TREBAY Published: November 25, 2007 | |

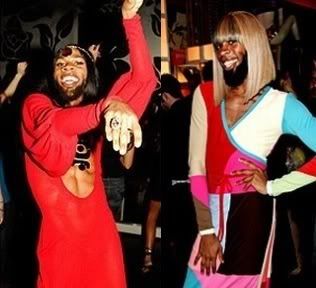

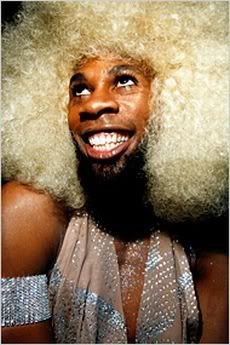

Lenox Fontaine for NYT; Bryan Bedder/Getty Images AROUND THE TOWN Andre J. attending a party in his honor at Runway and at a party in April. | |

| WHAT follows is, in brief (well, not so brief), the curious tale of how a handsome black man who can also look an awful lot like a beautiful black woman, except with better legs than most and a beard, happened to end up on the November cover of French Vogue.

The time was summer 2007. The man, who goes by the name Andre J., and who was born Andre Johnson 28 years ago in Newark, and who is a sometime party promoter and former perfume salesclerk at Lord & Taylor and former publicist at Patricia Field's boutique and current downtown personage (an "It" person, as he was termed in Paper magazine), was running out of his apartment on Thompson Street in the Village for lunch. It was a hot day. On this particular scorcher, Andre J. had chosen to stay cool in a neon green caftan and gold gladiator sandals. His hair, which, pulled taut, measures 24 inches in length and which he usually wears in a bouffant nimbus that gives him the appearance, as a magazine stylist recently remarked, of "a big Afro-daisy," was dressed that day in a 1970s Wet & Wild style and covered in a enormous white turban à la Nina Simone. This was not an unusual grab-a-sandwich ensemble, as Andre J. is quick to point out. "That's me every day, honey," Andre J. said on Friday, right before a party at a club called Runway to honor his election to the elite cover girl sorority, Gallic chapter. "Most people are conditioned to think of a black man looking a certain way," Andre J. went on. "They only think of the ethnic man in XXX jeans and Timberlands, and here Andre J. comes along with a pair of hot shorts and a caftan or maybe flip-flops or cowboy boots or a high, high heel." And so, Andre J. was running out for a sandwich and who should he bump into but Joe McKenna, the stylist who is the secret weapon behind the success of many, many very celebrated designers? Mr. McKenna was on the phone at the time. The person on the other end was Bruce Weber, the celebrated photographer of, among other things, dreamily homoerotic calendar art for Abercrombie & Fitch. | |

David X. Prutting/Patrick McMullan for NYT. THAT SMILE, THAT HAIR Think of Andre J. as rolling out his own stage every day. | |

When Mr. McKenna spotted Andre J., he immediately put Mr. Weber on hold. Mr. McKenna then called out to Andre J., whom he had met before and had once suggested for a V magazine pictorial photographed by Vinoodh Matadin and Inez van Lamsweerde. "Andre," said Mr. McKenna, "you look amazing!" ACTUALLY, he did not say it in quite that way. It happens that the adjective "amazing," pronounced with a bunch of superfluous vowels, is how fashion types, and also certain urban gay men and also one or two tuned-in heterosexual copycats, lately express their approval. Amazing has replaced such locutions as "genius" and "major," which today sound even more old-hat than "fabulous." "You look amaaaaazing," Mr. McKenna said. And, of course, Andre J. did. "I always do," remarked the man who appeared in that V magazine pictorial wearing a Farrah Fawcett-style coiffure and a gold necklace that read "Legendary" and skinny, skinny Judi Rosen cigarette jeans, and who, for a time, had a day job at a boutique on Melrose Avenue in Los Angeles, where his usual work uniform was a big fur hat and a beige fishnet shirt with a lot of holes in it and jeans so low cut that they exposed the pubic hair that he has since shaved off, and who has also appeared three times on Jay Leno, in cameo segments devoted to human curiosities. "I went to L.A. for a while for the sex and the fame," said Andre J., who, as if life were a lyric from a Burt Bacharach song, happened in those early years of this century to live for a time in a $60 a night motel on Sunset Strip, a situation that required him to change clothes after work each night, so as not to be mistaken on the street for a transsexual prostitute. This is perhaps the place to mention that Andre J. does not consider himself a cross dresser. Except to the extent each of us getting dressed assumes some kind of persona, his style is not drag. He is not a person in regard to whom the prefix "trans-" obtains. It is simply that Andre J., who was raised in a loving single-mother household in a housing project in Newark with the uplifting name Academy Spires, is in no sense confined by the conventions of gender. Think of him as a performance artist who rolls out his own stage every day. "I'm just expressing myself and not hurting anyone and taking myself to a place where I want to be, a place where the world is beautiful," said Andre J., who decided that, having conquered Hollywood, in his manner, it was time to return home. "I packed up all my hot shorts, which really didn't require all that much packing," he said. He returned not to Newark but to the Village and to Thompson Street and got jobs as a party host at Lotus on Tuesdays and Hiro on Sundays and continued to write in the journal he has kept for years. "Journaling" as he calls it, is a key to understanding the "positivity and optimism" that Andre J. says is what draws people to him, and also a way for him to "write things that I need to say that I can't say to anyone, but that, if I put them on paper, go into the universe for the universe to hear." The universe was apparently picking up the Andre J. signal on that afternoon last summer, because Mr. McKenna said to Mr. Weber, as Andre J. tells it, "You have to see Andre and shoot him." At the time, Andre J. smiled politely, and remained inwardly less positive. "This is New York City, honey," he said. "Everybody will tell you everything." Then he went and got lunch. To the surprise of Andre J., and ultimately of people accustomed to seeing the same bland blonds on fashion magazine covers, the next thing that happened, after an interval of several weeks, was that an assistant to Mr. Weber called Andre and said, "Bruce would like to set up some time with you," and Andre J. went to that meeting in a caftan over a pair of black jeweled panties and Mr. Weber took three Polaroid pictures and Andre left and soon thereafter received another call, from the assistant again, to say that Mr. Weber would like Andre J. to come to Montauk to be photographed for French Vogue. "I did not know what to say," Andre J. said. "Actually, I did know what to say. I said, 'Yes.'" | |

Neil Rasmus/Patrick McMullan for NYT. Posing with Malik Sterling, a regular on the Manhattan social scene, at an event for Patrick McMullan's book "Glamour Girls" in September; | |

| And so it was that Andre J. who had most recently been style-channeling Cher and compulsively Google-searching the late Detroit-born model and beauty and heroin addict Donyale Luna, and evolving his personal appearance to express what he thinks of as "a 60s, not mod, but mod-ish, and hippie look" that also contains elements of 1970s blaxploitation films found his way to Mr. Weber's compound by bus. "The night before, honey, I prayed and I journaled," he said. "Discretion and decorum is always important to Andre J., but when I got there and I saw Carolyn Murphy and Carine Roitfeld," he added, referring to, respectively, the model and the editor of French Vogue, "I almost wanted to faint." He did not faint. He kept his composure. "I wanted to experience that beautiful day in pure bliss," he said, "So I did not impose my own thoughts or views." This is just as well since Ms. Roitfeld has strong style views of her own, including the opinion that the pictures Mr. Weber shot with Andre J. seemed, as she said this week, "the more fresh" of the various images they captured. "There is not a special message in the cover, I just loved it," said Ms. Roitfeld, who on that hot sticky day in Montauk gave Andre J. some ankle boots to wear and a big cocktail ring and a blue neoprene Burberry trench coat that showed off his unbelievable legs. "It fit like a glove and it was immediately showtime," Andre J said. James Brown was playing on the set as Mr. Weber shot Andre J. spinning like, as he put it,Diana Ross in "Mahogany." He shot him next with Ms. Murphy. Then he thanked him, and Andre J. got dressed again in his travel caftan and went back to New York. MONTHS passed and Andre J. was coming home from church one Sunday when a friend called to give him the news that he was on the cover of French Vogue. "I said, 'This is not funny, don't play with me,'" said Andre J. "Then my friend said, 'Google.' And I went home and Googled and, you know what? There I was, honey, right where my heroes like Madonna and Mario Testino and Steven Klein can see me. Anything you love you can sell, honey, and I sold it. Andre J. is a part of history." | |