| Friday, Jun. 05, 2009.

How Twitter Will Change the Way We Live.

By Steven Johnson |

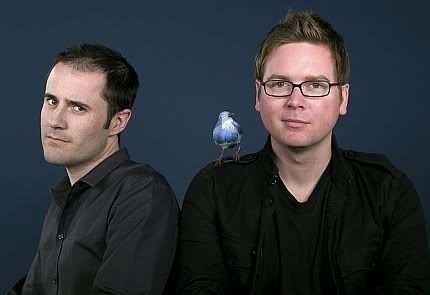

Evan Williams and Biz Stone of Twitter. Evan Williams and Biz Stone of Twitter. |

The one thing you can say for certain about Twitter is that it makes a terrible first impression. You hear about this new service that lets you send 140-character updates to your "followers," and you think, Why does the world need this, exactly? It's not as if we were all sitting around four years ago scratching our heads and saying, "If only there were a technology that would allow me to send a message to my 50 friends, alerting them in real time about my choice of breakfast cereal." I, too, was skeptical at first. I had met Evan Williams, Twitter's co-creator, a couple of times in the dotcom '90s when he was launching Blogger.com. Back then, what people worried about was the threat that blogging posed to our attention span, with telegraphic, two-paragraph blog posts replacing long-format articles and books. With Twitter, Williams was launching a communications platform that limited you to a couple of sentences at most. What was next? Software that let you send a single punctuation mark to describe your mood? (See the top 10 ways Twitter will change American business.) And yet as millions of devotees have discovered, Twitter turns out to have unsuspected depth. In part this is because hearing about what your friends had for breakfast is actually more interesting than it sounds. The technology writer Clive Thompson calls this "ambient awareness": by following these quick, abbreviated status reports from members of your extended social network, you get a strangely satisfying glimpse of their daily routines. We don't think it at all moronic to start a phone call with a friend by asking how her day is going. Twitter gives you the same information without your even having to ask. The social warmth of all those stray details shouldn't be taken lightly. But I think there is something even more profound in what has happened to Twitter over the past two years, something that says more about the culture that has embraced and expanded Twitter at such extraordinary speed. Yes, the breakfast-status updates turned out to be more interesting than we thought. But the key development with Twitter is how we've jury-rigged the system to do things that its creators never dreamed of. In short, the most fascinating thing about Twitter is not what it's doing to us. It's what we're doing to it. The Open Conversation Earlier this year I attended a daylong conference in Manhattan devoted to education reform. Called Hacking Education, it was a small, private affair: 40-odd educators, entrepreneurs, scholars, philanthropists and venture capitalists, all engaged in a sprawling six-hour conversation about the future of schools. Twenty years ago, the ideas exchanged in that conversation would have been confined to the minds of the participants. Ten years ago, a transcript might have been published weeks or months later on the Web. Five years ago, a handful of participants might have blogged about their experiences after the fact. (See the top 10 celebrity Twitter feeds.) But this event was happening in 2009, so trailing behind the real-time, real-world conversation was an equally real-time conversation on Twitter. At the outset of the conference, our hosts announced that anyone who wanted to post live commentary about the event via Twitter should include the word #hackedu in his 140 characters. In the room, a large display screen showed a running feed of tweets. Then we all started talking, and as we did, a shadow conversation unfolded on the screen: summaries of someone's argument, the occasional joke, suggested links for further reading. At one point, a brief argument flared up between two participants in the room a tense back-and-forth that transpired silently on the screen as the rest of us conversed in friendly tones. At first, all these tweets came from inside the room and were created exclusively by conference participants tapping away on their laptops or BlackBerrys. But within half an hour or so, word began to seep out into the Twittersphere that an interesting conversation about the future of schools was happening at #hackedu. A few tweets appeared on the screen from strangers announcing that they were following the #hackedu thread. Then others joined the conversation, adding their observations or proposing topics for further exploration. A few experts grumbled publicly about how they hadn't been invited to the conference. Back in the room, we pulled interesting ideas and questions from the screen and integrated them into our face-to-face conversation. When the conference wrapped up at the end of the day, there was a public record of hundreds of tweets documenting the conversation. And the conversation continued if you search Twitter for #hackedu, you'll find dozens of new comments posted over the past few weeks, even though the conference happened in early March. Injecting Twitter into that conversation fundamentally changed the rules of engagement. It added a second layer of discussion and brought a wider audience into what would have been a private exchange. And it gave the event an afterlife on the Web. Yes, it was built entirely out of 140-character messages, but the sum total of those tweets added up to something truly substantive, like a suspension bridge made of pebbles. The Super-Fresh Web The basic mechanics of Twitter are remarkably simple. Users publish tweets those 140-character messages from a computer or mobile device. (The character limit allows tweets to be created and circulated via the SMS platform used by most mobile phones.) As a social network, Twitter revolves around the principle of followers. When you choose to follow another Twitter user, that user's tweets appear in reverse chronological order on your main Twitter page. If you follow 20 people, you'll see a mix of tweets scrolling down the page: breakfast-cereal updates, interesting new links, music recommendations, even musings on the future of education. Some celebrity Twitterers most famously Ashton Kutcher have crossed the million-follower mark, effectively giving them a broadcast-size audience. The average Twitter profile seems to be somewhere in the dozens: a collage of friends, colleagues and a handful of celebrities. The mix creates a media experience quite unlike anything that has come before it, strangely intimate and at the same time celebrity-obsessed. You glance at your Twitter feed over that first cup of coffee, and in a few seconds you find out that your nephew got into med school and Shaquille O'Neal just finished a cardio workout in Phoenix. (See excerpts from the world's most popular Twitterers.) In the past month, Twitter has added a search box that gives you a real-time view onto the chatter of just about any topic imaginable. You can see conversations people are having about a presidential debate or the American Idol finale or Tiger Woods or a conference in New York City on education reform. For as long as we've had the Internet in our homes, critics have bemoaned the demise of shared national experiences, like moon landings and "Who Shot J.R." cliff hangers the folkloric American living room, all of us signing off in unison with Walter Cronkite, shattered into a million isolation booths. But watch a live mass-media event with Twitter open on your laptop and you'll see that the futurists had it wrong. We still have national events, but now when we have them, we're actually having a genuine, public conversation with a group that extends far beyond our nuclear family and our next-door neighbors. Some of that conversation is juvenile, of course, just as it was in our living room when we heckled Richard Nixon's Checkers speech. But some of it is moving, witty, observant, subversive. Skeptics might wonder just how much subversion and wit is conveyable via 140-character updates. But in recent months Twitter users have begun to find a route around that limitation by employing Twitter as a pointing device instead of a communications channel: sharing links to longer articles, discussions, posts, videos anything that lives behind a URL. Websites that once saw their traffic dominated by Google search queries are seeing a growing number of new visitors coming from "passed links" at social networks like Twitter and Facebook. This is what the naysayers fail to understand: it's just as easy to use Twitter to spread the word about a brilliant 10,000-word New Yorker article as it is to spread the word about your Lucky Charms habit. Put those three elements together social networks, live searching and link-sharing and you have a cocktail that poses what may amount to the most interesting alternative to Google's near monopoly in searching. At its heart, Google's system is built around the slow, anonymous accumulation of authority: pages rise to the top of Google's search results according to, in part, how many links point to them, which tends to favor older pages that have had time to build an audience. That's a fantastic solution for finding high-quality needles in the immense, spam-plagued haystack that is the contemporary Web. But it's not a particularly useful solution for finding out what people are saying right now, the in-the-moment conversation that industry pioneer John Battelle calls the "super fresh" Web. Even in its toddlerhood, Twitter is a more efficient supplier of the super-fresh Web than Google. If you're looking for interesting articles or sites devoted to Kobe Bryant, you search Google. If you're looking for interesting comments from your extended social network about the three-pointer Kobe just made 30 seconds ago, you go to Twitter. From Toasters to Microwaves Because Twitter's co-founders Evan Williams, Biz Stone and Jack Dorsey are such a central-casting vision of start-up savvy (they're quotable and charming and have the extra glamour of using a loft in San Francisco's SoMa district as a headquarters instead of a bland office park in Silicon Valley) much of the media interest in Twitter has focused on the company. Will Ev and Biz sell to Google early or play long ball? (They have already turned down a reported $500 million from Facebook.) It's an interesting question but not exactly a new plotline. Focusing on it makes you lose sight of the much more significant point about the Twitter platform: the fact that many of its core features and applications have been developed by people who are not on the Twitter payroll. |

This is not just a matter of people finding a new use for a tool designed to do something else. In Twitter's case, the users have been redesigning the tool itself. The convention of grouping a topic or event by the "hashtag" #hackedu or #inauguration was spontaneously invented by the Twitter user base (as was the convention of replying to another user with the @ symbol). The ability to search a live stream of tweets was developed by another start-up altogether, Summize, which Twitter purchased last year. (Full disclosure: I am an adviser to one of the minority investors in Summize.) Thanks to these innovations, following a live feed of tweets about an event political debates or Lost episodes has become a central part of the Twitter experience. But just 12 months ago, that mode of interaction would have been technically impossible using Twitter. It's like inventing a toaster oven and then looking around a year later and seeing that your customers have of their own accord figured out a way to turn it into a microwave. (See the 50 best inventions of 2008.) One of the most telling facts about the Twitter platform is that the vast majority of its users interact with the service via software created by third parties. There are dozens of iPhone and BlackBerry applications all created by enterprising amateur coders or small start-ups that let you manage Twitter feeds. There are services that help you upload photos and link to them from your tweets, and programs that map other Twitizens who are near you geographically. Ironically, the tools you're offered if you visit Twitter.com have changed very little in the past two years. But there's an entire Home Depot of Twitter tools available everywhere else. As the tools have multiplied, we're discovering extraordinary new things to do with them. Last month an anticommunist uprising in Moldova was organized via Twitter. Twitter has become so widely used among political activists in China that the government recently blocked access to it, in an attempt to censor discussion of the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. A service called SickCity scans the Twitter feeds from multiple urban areas, tracking references to flu and fever. Celebrity Twitterers like Kutcher have directed their vast followings toward charitable causes (in Kutcher's case, the Malaria No More organization). Social networks are notoriously vulnerable to the fickle tastes of teens and 20-somethings (remember Friendster?), so it's entirely possible that three or four years from now, we'll have moved on to some Twitter successor. But the key elements of the Twitter platform the follower structure, link-sharing, real-time searching will persevere regardless of Twitter's fortunes, just as Web conventions like links, posts and feeds have endured over the past decade. In fact, every major channel of information will be Twitterfied in one way or another in the coming years: News and opinion. Increasingly, the stories that come across our radar news about a plane crash, a feisty Op-Ed, a gossip item will arrive via the passed links of the people we follow. Instead of being built by some kind of artificially intelligent software algorithm, a customized newspaper will be compiled from all the articles being read that morning by your social network. This will lead to more news diversity and polarization at the same time: your networked front page will be more eclectic than any traditional-newspaper front page, but political partisans looking to enhance their own private echo chamber will be able to tune out opposing viewpoints more easily. Searching. As the archive of links shared by Twitter users grows, the value of searching for information via your extended social network will start to rival Google's approach to the search. If you're looking for information on Benjamin Franklin, an essay shared by one of your favorite historians might well be more valuable than the top result on Google; if you're looking for advice on sibling rivalry, an article recommended by a friend of a friend might well be the best place to start. Advertising. Today the language of advertising is dominated by the notion of impressions: how many times an advertiser can get its brand in front of a potential customer's eyeballs, whether on a billboard, a Web page or a NASCAR hood. But impressions are fleeting things, especially compared with the enduring relationships of followers. Successful businesses will have millions of Twitter followers (and will pay good money to attract them), and a whole new language of tweet-based customer interaction will evolve to keep those followers engaged: early access to new products or deals, live customer service, customer involvement in brainstorming for new products. Not all these developments will be entirely positive. Most of us have learned firsthand how addictive the micro-events of our personal e-mail inbox can be. But with the ambient awareness of status updates from Twitter and Facebook, an entire new empire of distraction has opened up. It used to be that you compulsively checked your BlackBerry to see if anything new had happened in your personal life or career: e-mail from the boss, a reply from last night's date. Now you're compulsively checking your BlackBerry for news from other people's lives. And because, on Twitter at least, some of those people happen to be celebrities, the Twitter platform is likely to expand that strangely delusional relationship that we have to fame. When Oprah tweets a question about getting ticks off her dog, as she did recently, anyone can send an @ reply to her, and in that exchange, there is the semblance of a normal, everyday conversation between equals. But of course, Oprah has more than a million followers, and that isolated query probably elicited thousands of responses. Who knows what small fraction of her @ replies she has time to read? But from the fan's perspective, it feels refreshingly intimate: "As I was explaining to Oprah last night, when she asked about dog ticks ..." End-User Innovation The rapid-fire innovation we're seeing around Twitter is not new, of course. Facebook, whose audience is still several times as large as Twitter's, went from being a way to scope out the most attractive college freshmen to the Social Operating System of the Internet, supporting a vast ecosystem of new applications created by major media companies, individual hackers, game creators, political groups and charities. The Apple iPhone's long-term competitive advantage may well prove to be the more than 15,000 new applications that have been developed for the device, expanding its functionality in countless ingenious ways. The history of the Web followed a similar pattern. A platform originally designed to help scholars share academic documents, it now lets you watch television shows, play poker with strangers around the world, publish your own newspaper, rediscover your high school girlfriend and, yes, tell the world what you had for breakfast. Twitter serves as the best poster child for this new model of social creativity in part because these innovations have flowered at such breathtaking speed and in part because the platform is so simple. It's as if Twitter's creators dared us to do something interesting by giving us a platform with such draconian restrictions. And sure enough, we accepted the dare with relish. Just 140 characters? I wonder if I could use that to start a political uprising. (See the 25 best blogs of 2009.) The speed with which users have extended Twitter's platform points to a larger truth about modern innovation. When we talk about innovation and global competitiveness, we tend to fall back on the easy metric of patents and Ph.D.s. It turns out the U.S. share of both has been in steady decline since peaking in the early '70s. (In 1970, more than 50% of the world's graduate degrees in science and engineering were issued by U.S. universities.) Since the mid-'80s, a long progression of doomsayers have warned that our declining market share in the patents-and-Ph.D.s business augurs dark times for American innovation. The specific threats have changed. It was the Japanese who would destroy us in the '80s; now it's China and India. But what actually happened to American innovation during that period? We came up with America Online, Netscape, Amazon, Google, Blogger, Wikipedia, Craigslist, TiVo, Netflix, eBay, the iPod and iPhone, Xbox, Facebook and Twitter itself. Sure, we didn't build the Prius or the Wii, but if you measure global innovation in terms of actual lifestyle-changing hit products and not just grad students, the U.S. has been lapping the field for the past 20 years. How could the forecasts have been so wrong? The answer is that we've been tracking only part of the innovation story. If I go to grad school and invent a better mousetrap, I've created value, which I can protect with a patent and capitalize on by selling my invention to consumers. But if someone else figures out a way to use my mousetrap to replace his much more expensive washing machine, he's created value as well. We tend to put the emphasis on the first kind of value creation because there are a small number of inventors who earn giant paydays from their mousetraps and thus become celebrities. But there are hundreds of millions of consumers and small businesses that find value in these innovations by figuring out new ways to put them to use. There are several varieties of this kind of innovation, and they go by different technical names. MIT professor Eric von Hippel calls one "end-user innovation," in which consumers actively modify a product to adapt it to their needs. In its short life, Twitter has been a hothouse of end-user innovation: the hashtag; searching; its 11,000 third-party applications; all those creative new uses of Twitter some of them banal, some of them spam and some of them sublime. Think about the community invention of the @ reply. It took a service that was essentially a series of isolated microbroadcasts, each individual tweet an island, and turned Twitter into a truly conversational medium. All of these adoptions create new kinds of value in the wider economy, and none of them actually originated at Twitter HQ. You don't need patents or Ph.D.s to build on this kind of platform. This is what I ultimately find most inspiring about the Twitter phenomenon. We are living through the worst economic crisis in generations, with apocalyptic headlines threatening the end of capitalism as we know it, and yet in the middle of this chaos, the engineers at Twitter headquarters are scrambling to keep the servers up, application developers are releasing their latest builds, and ordinary users are figuring out all the ingenious ways to put these tools to use. There's a kind of resilience here that is worth savoring. The weather reports keep announcing that the sky is falling, but here we are millions of us sitting around trying to invent new ways to talk to one another. Johnson is the author of six books, most recently The Invention of Air, and a co-founder of the local-news website outside.in |

RELATED

|

Open article at time.com

| | About TIME Terms of Service | | |